Big Win for Taxpayers Against Corporate Tax Dodgers

Washington – If you think our tax system is rigged in favor of U.S. multi-national corporations, Exhibit A is the laws passed by Congress that have let nearly 50 major American companies renounce their U.S. citizenship and merge with foreign companies in order to duck U.S. corporate income taxes.

In the anodyne lingo of Wall Street, these are called “corporate inversions,” and the latest was Pfizer’s blockbuster $152 billion merger with Allergan, maker of Botox, based in Dublin. Announcing the deal last November, Pfizer made no secret that in giving up its U.S. citizenship to become an Irish corporation, its goal was to take advantage of Ireland’s new low 6.3% tax rate and to reduce its American taxes. Outside tax specialists calculated Pfizer would save $35 billion in U.S. taxes.

(CC) Michael Fleshman

As President Obama commented, such deals may seem blatantly unpatriotic, but for some time it has been perfectly legal for American companies to flip their home address without changing their CEO or their basic operations through foreign mergers that will cost Uncle Sam tens of billions in lost corporate tax revenues over the next decade, dumping an extra burden on average taxpayers.“It sticks the rest of us with the tab,” President Obama says, “and it makes hardworking Americans feel like the deck is stacked agains them.”

Obama Administration – Putting on the Squeeze

With pro-business members of Congress, mostly Republicans, stalling legislation to close what the President calls “the most insidious tax loophole out there” for Corporate America, the Treasury Department has twice revised tax rules to deter corporate inversions by making them less financially attractive. Those earlier efforts failed to shut the door, but just this week, the Treasury hit pay dirt.

Within hours of its announcing a third new set of rules, Allergan’s stock plummeted and within 24 hours, Pfizer disclosed that it plans to cancel its merger with Allergan. Treasury and IRS tax specialists had been racing to complete these rules before the Pfizer-Allergan deal was consummated. The stopper was a complex regulation that blocks companies from shifting profits earned in the U.S. to their overseas partner by taking out huge loans from their foreign parent company and then claiming a whopping tax deduction for interest on the loans, plus some specific regulations versus foreign companies that engage in “serial inversions.”

Good progress but not a final solution, Treasury officials admitted. “These actions took away some of the economic benefits of inverting and helped slow the pace of these transactions,” commented Treasury Secretary Jacob Liu, “but we know that companies will continue to seek new and creative ways to relocate their tax residence to avoid paying taxes here at home.” For a broader fix, Congress must rewrite the corporate tax laws.

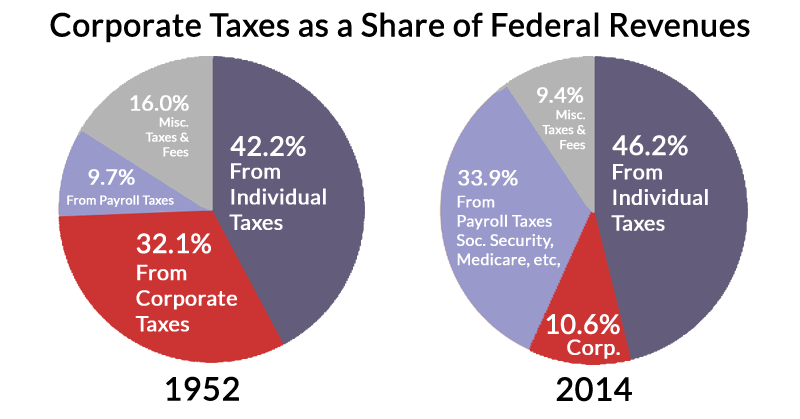

Steep Drop in Corporate Share of Tax Revenues

Inversions are just the newest gimmick in a long-term trend that has eroded America’s corporate tax base. Since the 1950s, the corporate share of federal tax revenues has fallen steeply from over 30% to just 10% percent today – thanks, not only to a lower corporate tax rate but to $1.2 trillion in corporate tax loopholes passed by Congress.

Foreign tax havens have become the new norm for Corporate America. Major multi-nationals find financial hideaways like Bermuda, Puerto Rico or the Cayman islands where they can set up shell affiliates, often little more than an small office with a big bank account, where they can stash their overseas profits and escape having to pay U.S. taxes.

In 2014, that practice was so pervasive that nearly three-fourths of Fortune 500 companies booked profits to foreign tax havens, according to a study by Citizens for Tax Justice and US PIRG. In all, U.S. companies were hoarding $2.1 trillion in profits offshore – enough to generate $620 billion in U.S. taxes if American companies had brought all their earnings back home to the United States.

Apple Transfers Patents to Escape U.S. Taxes

Even on earnings generated inside the U.S., companies can hop profits over borders with accounting gimmickry. High Tech companies like Apple shift ownership of their prime patents to overseas affiliates. Even though new technology for Apple iPhones and iPads is mostly invented in California for obtaining U.S. patents, Apple says the patents belong to its subsidiary in low-tax Ireland, so that’s where the profits flow and where taxes are paid.

Ditto, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Gilead, Starbucks, FedEx, Pepsico and many others. Starbucks gave ownership of its secret formulas for roasting coffee to a subsidiary in the Netherlands and got a sweetheart tax deal. Such an outlandish deal, in fact, that European regulators said it violated EU rules on fair competition. So they ordered Starbucks to pay the Dutch government $34 million in back taxes.

Ditto, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Gilead, Starbucks, FedEx, Pepsico and many others. Starbucks gave ownership of its secret formulas for roasting coffee to a subsidiary in the Netherlands and got a sweetheart tax deal. Such an outlandish deal, in fact, that European regulators said it violated EU rules on fair competition. So they ordered Starbucks to pay the Dutch government $34 million in back taxes.

Caterpillar, which makes tractors and heavy earth-movers in Illinois for the global market, concocted a scheme that saved it $2.4 billion in U.S. taxes by having its Swiss subsidiary send out billing invoices to its customers worldwide. So even though Caterpillar tractors were proudly marketed as “Made in America,” Switzerland is where the customers paid their bills and where Caterpillar was taxed – at its own specially negotiated rate of 5%.

If you’re tempted to scream, “There ought to be a law against it!” get in line.

Not only has President Obama called for reforms to block corporate inversion mergers, curb the use of tax havens and tax overseas corporate earnings, but Republican billionaire-candidate Donald Trump has denounced Pfizer’s inversion deal as “disgusting” and said, “Our politicians should be ashamed.”

In fact, the Pfizer-Allergan merger prompted talk of reform on Capitol Hill. “It’s imperative we explore what actions can be taken now,” said Utah’s Republican Senator Orrin Hatch, chair of the Senate Finance Committee. “The best way to resolve these issues would be through comprehensive tax overhaul.” That’s a common theme in Congress, but so far Republican majorities in both houses have refused to take action.

How Big Business Blocked Corporate Tax Reform

The most promising push for corporate tax reform in Congress in recent years began with strong corporate backing and was painstakingly stitched together in 2014 by Michigan Republican Congressman Dave Camp, a pro-business conservative who then chaired the powerful House Ways and Means Committee.

Former Rep. Dave Camp, (R-Mich.) authored major tax reform plan but got shot down by his former corporate supporters. (CC) House GOP

For years, business leaders had clamored for a cut in the corporate tax rate and Camp complied, proposing a cut from 35% to 25%. To raise revenues to offset that cut, Camp proposed closing some big corporate tax loopholes, including the tax exemption on overseas earnings.

Two days after unveiling his tax plan in February 2014, Camp flew to Park City Utah expecting to be feted at a big campaign fund-raiser attended by major corporate lobbyists. Instead, Camp ran into a buzz saw of opposition. Suddenly, the corporate lobbyists who had pushed him into tax reform were angry at him for attacking their loopholes. Within days, they had jawboned 50 congressional Republicans to publicly oppose Camp’s bill.

Corporate opposition killed Camp’s reform plan before it got off the ground, and Camp’s shipwreck became an object lesson for Congress on Corporate America’s ability to block action on tax issues.

Oregon: Test Ground for Higher Corporate Taxes

With Congress stymied, the issues of higher corporate taxes has moved to states like Oregon, where a ballot initiative this year seeks to raise $3 billion through a 2.5% increase in corporate taxes to fund spending on schools, health care, senior services, and higher education. “Our corporations have to be held accountable,” declares Kayse Jama, executive director of Unite Oregon, calling for passage of Measure 97 that would create largest flow of tax revenue in any state this year.

“It’s time for corporations to pay their share,” declares Governor Kate Brown, a Democrat running for re-election. It would be “absurd and ludicrous,” says Brown, to cut back or put a lid on needed programs to avoid raising taxes, devastating the most vulnerable people in Oregon. But her Republican opponent, William Pierce, opposes the tax increase, questioning whether state government can generate jobs and a fairer economy, asserting that it is time to move Oregon from “the hard left toward the center.”

Corporations like Amazon, General Motors and the Kroger/Fred Meyer grocery chain are taking no chances, They have raised $8 million to fight the corporate tax initiative, gearing up to spend four times as much as Measure 97’s supporters, and warning Oregonians that companies will pass along the cost of higher taxes to consumers by raising prices, cutting jobs or moving out of state.

Corporate America – $5.8 Billion to Buy Influence

All across the country, Corporate America is quietly and often covertly financing business-friendly candidates who can eventually be counted on to oppose corporate tax increases when that issue comes up in Congress. The Sunlight Foundation, which tracks political money, reports that from 2007 to 2012, America’s 200 most politically active companies spent a whopping $5.8 billion on political campaigns and lobbying in Washington.

Top Corporate donors to congressional campaigns state-by-state – Source: U.S. PIRG

For 2016, corporate funders are already busy targeting congressional races. The Public Interest Research Group (US-PIRG) identified the biggest corporate donor in each of the 50 states: Lockheed-Martin in Texas and Colorado; Fedex in Tennessee; AT&T in Florida and Iowa; Home Depot in Alaska; Koch Industries in Kansas and West Virginia; Comcast in Pennsylvania; Nike in Oregon; Honeywell in New Jersey, North Carolina, Indiana, Utah, Nebraska, and Montana, all seeking friends for business in the next Congress.

The cash flow from Mega donors into campaigns changes constantly but the trend for the 2015-16 election cycle is obvious. The Center for Responsive Politics reports that funds spent by SuperPACs and other outside groups has already topped $300 million, more than triple the level at this stage of the 2012 presidential campaign. According to the Center’s campaign experts, spending by anchor campaign contributors like major U.S. corporations and the U.S. chamber of commerce “has ratcheted up at a pace not seen in previous cycles.”

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.