Student Debt:

Student Debt:

Drag on Job and Millennials

Student Debt:

Student Debt:Drag on Job and Millennials

A Financial Cancer for America

College education, long a prime aspiration of the American Dream, is in jeopardy today because massive student debt has become a financial cancer with lethal consequences for the entire nation. Student debt not only levies a relentless squeeze on millions of average families, but it also imposes a hidden price on all Americans because it is a drag on our whole economy.

Student debt is altering the economic behavior of the millennial generation. So many young people come out of college deep in the red that in order to save money, they live with their parents in record numbers instead of renting or buying their own homes. For the first time since 1880, the Pew Research Center reported in May 2016, nearly one-third of 18-to-34-year-olds (32.1%) live with their parents – more than the percentage living with a spouse, romantic other, or with roommates.

Today’s college graduates delay getting married, so much so that the median age for first marriages has shot up from 20.1 years of age for women and 22.5 for men in 1956 to 27.1 years of age for women and 29.2 years for men nowadays. Similarly, the younger generation tends to postpone the purchase of cars and other big-ticket items like home appliances that help drive U.S. economic growth. With tens of millions of young adults spending less, the economy creeps along more slowly.

The impact is large because student debt is so enormous. More than 45 million Americans owe more than $1.7 trillion in student debt– more than the credit card debt of the entire country, and it is rising at the rate of $100 billion a year. Student debt is epidemic. Nearly 70% of students who earn a bachelor’s degree are in debt. In all, 38 million people – one in every eight Americans, not just young people but middle-aged and even people in the 60s.

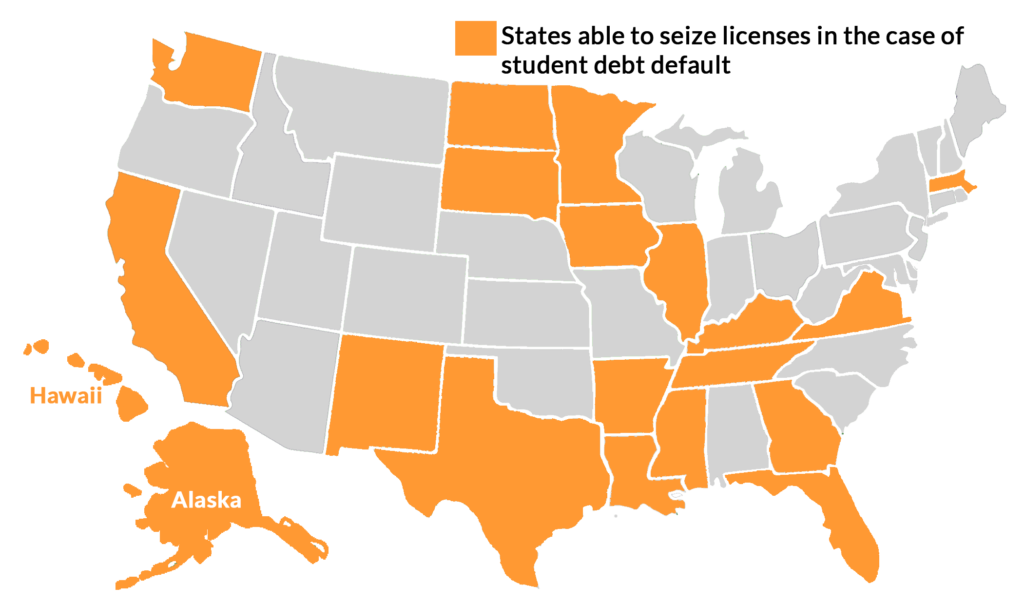

Some states are particularly harsh on people who fall behind o n repaying their student debt, often revoking professional licenses or suspending drivers’ licenses, moves that can derail careers and deprive people of the income they need to repay their student loans. Twenty states have laws empowering state agencies to revoke or suspend the licenses of lawyers, real estate brokers, nurses, teachers, firefighters, and massage therapists. Recently, the New York Times identified more than 8,700 cases where professional licenses were taken away or put at risk of suspension because of delay or default on student loans. In some cases, people have lost their jobs and been plunged even deeper into debt.

n repaying their student debt, often revoking professional licenses or suspending drivers’ licenses, moves that can derail careers and deprive people of the income they need to repay their student loans. Twenty states have laws empowering state agencies to revoke or suspend the licenses of lawyers, real estate brokers, nurses, teachers, firefighters, and massage therapists. Recently, the New York Times identified more than 8,700 cases where professional licenses were taken away or put at risk of suspension because of delay or default on student loans. In some cases, people have lost their jobs and been plunged even deeper into debt.

Student Debt Hits Upper Income Brackets

Individual debt has shot up sharply since 2000. Today, the average debt at graduation for students at four-year colleges is $36,693, roughly double what it was in 2001 (adjusted for inflation). For graduate students, the median debt is $59,000, up from $38,000 in 2004. More than 3.2 million Americans have individual student loan debt of $100,000 or more.

Student debt spreads like crabgrass. It just keeps sprawling. Today, it is no longer just lower-income families but upper middle class and high-income families that are afflicted with ever-mounting college debt. In 2012, half of the college graduates from high-income families borrowed money to go to college, double the percentage in the early 1990s. Among upper-middle-class families, 62% of students leave college with a debt hangover, nearly double the rate two decades ago.

What Drives the Repayment Crisis?

What worries parents and policy-makers most is not just the mounting volume of student debt but the repayment crisis. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau estimates that more than seven million people are in default on over $100 billion in student loan balances, meaning that on those loans, no payment has been made for nine months. Another $120 billion in loans is typically delinquent, meaning borrowers have missed their scheduled payment date. Most eventually catch up, but some sink into default.

The stakes of default or delinquency can be very high for borrowers because of the draconian powers of collection agencies. Unlike all other forms of debt, student loans are not discharged in bankruptcy. Moreover, lenders can garnishee wages and seize earned income tax credits and Social Security benefits for repayment on loans. And finally, default leaves an indelible black stain on credit reports of borrowers, crippling their future ability to obtain credit for lifetime purchases, such as homes and cars.

Fatal Mismatch: High Costs + Low Pay

One major cause of the high rates of defaults and delinquencies is the mismatch between costs and benefits – the fast buildup of college bills and the much slower, often uncertain and erratic earning power of most college graduates entering a difficult job market.

This mismatch was particularly acute in the 1990s when the standard repayment period for student loans from private lenders and on federal direct loans was ten years. In the late 1990s, the Clinton Administration stretched out the repayment period on government loans to 25 years, but only one in seven student borrowers signed up for the more generous repayment timetable. Information was poor, the application process was complex and confusing, and private lenders stuck with the ten-year payback.

The economic downturn of 2008 and the nation’s painfully slow economic recovery made things worse. With jobs tight and entry-level pay for college graduates dropping below levels in the late 1990s, most recent graduates strain to make financial ends meet and still pay off their student loans, fueling the default rate.

How Did Student Debt Get So Bad?

There are two other major causes of exploding student debt. One is the new austerity economics – budget-cutting in state legislatures and in Congress that reflects a seismic shift in public attitudes about who should foot the bill for higher education. As states pay less, students carry a bigger share of the cost-load.

The other main cause is the rise of private, for-profit universities, bent on extracting tens of billions of dollars in profits from a market that depends on massive student borrowing, mainly from the federal government. The for-profit sector has left a trail of indentured student borrowers, trapped on a debt treadmill – unable to find steady jobs at good enough salaries to repay the high debts marketed to them by profiteering universities.

Dramatic Shift in Public Attitudes

These new trends mark a profound shift from the relatively recent past. After World War II, a grateful nation passed the G.I. Bill in 1944 that paid for the college education of returning veterans. And during the long Cold War with the Soviet Union, the idea took root that educating each new generation delivered valuable economic returns for the country.

In that era, college education for the rising generation was seen as a wise public investment. In state after state, taxpayers footed the lion’s share of the cost of public higher education, making state universities and colleges affordable.

That “we’re-all-in-it-together” philosophy has been turned upside-down in recent years. Higher education is no longer widely regarded as a public good, worthy of national investment. Now, it is seen more as a matter of personal gain and, therefore, personal responsibility: “You want it, you pay for it.”

That “we’re-all-in-it-together” philosophy has been turned upside-down in recent years. Higher education is no longer widely regarded as a public good, worthy of national investment. Now, it is seen more as a matter of personal gain and, therefore, personal responsibility: “You want it, you pay for it.”

This shift in public attitudes has generated a hefty shift in costs – from taxpayers to students and their families. And with roughly 70% of American college-level students in public university systems, this cost-shift has pyramided the growth of student debt.

The Burden Shift Hits Students

Over the past quarter-century, not only has the inflation-adjusted average tuition at four-year public colleges roughly doubled, but states have pushed for more of the increasing cost burden on students and their families.

In 1988, state and local governments paid more than three-quarters of the costs of educating students at public colleges and universities – an average of roughly $8,600 per student out of $11,300, according to the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. These figures do not include costs for room, board, books, or transportation. By 2013, a quarter of a century later, the average state and local share had dropped to just over 50% while the share paid by students and their families jumped from 24% to 44%.

What’s more, Congressional budget cuts and inflation have multiplied the debt of the most vulnerable students from low-income families. The Pell Grant program was created in 1972 to give these needy students a chance to go to college by giving them debt-free grants that do not have to be repaid – currently a maximum of $5,370 per year.

In the 2013-14 academic year, Pell grants totaling $33.7 billion were made to nine million students mostly from families with household incomes of $30,000 or less. Nearly two-thirds of African American undergraduates receive Pell grants, as do 51% of Latino undergraduates, according to the Education Trust.

Although President Obama doubled funding for the Pell program in 2010 through savings in other federal student loan programs, Congress has now cut Pell grants by $5 billion a year. The size of Pell grants has fallen well behind the inflation in college costs. As a result, the debt of Pell grant recipients has shot up by 90% over the past decade.

For-Profit Universities – Student-Debt Factories

For-Profit Universities – Student-Debt Factories

The most explosive growth in student debt and in loan defaults has come among the private sector, for-profit universities, some of which have compiled the lowest graduation and completion rates in U.S. higher education and left their students with high debt and poor job prospects. For-profit universities have tripled their enrollment in the past decade, but according to the Department of Education, they educate only 12% of college-level students nationwide yet they are responsible for 48% of student loan defaults.

The for-profit education sector has earned “the dubious distinction of having the highest debt levels, the highest default rates, and some of the lowest completion rates” in U.S. higher education, says Pauline Abernathy, Vice President of the Institute for College Assess and Success, a public interest advocacy organization.

One reason that for-profit universities play such a large role in the student debt crisis is that they have been so successful at capturing a lop-sided share of revenues from federal student loan programs – $32 billion in 2010, for example. Virtually all (96%) of the students who attend for-profit colleges borrow money, compared to 13% of the students at community colleges, 48% of students at public four-year universities, and 57% at four-year private nonprofit colleges.

For-Profits: A Questionable Record

As a business strategy, for-profit universities market their career-training courses aggressively as a path to good jobs, especially for Iraq and Afghan war veterans, and then help students file for federal loans. However, independent studies have shown that for-profit colleges do not typically deliver real job market advantages for their graduates. One survey done by scholars at the Rand Corporation and the University of Missouri reported that “applicants who attend for-profit colleges received less interest from employers than do applicants who attend public community colleges.”

A report on for-profits by the U. S. Senate Health Education Labor and Pension issued these disturbing findings: (a) more than half of the students at for-profits withdrew without a degree, undermining the promise of good career training; (b) more than one in five students defaulted on student loans; (c) for-profit colleges spent $4.2 billion on high-pressure recruiting and marketing in one year alone, but spent less on instruction, percentage-wise, than public universities; and (d) presidents of for-profit universities were paid an average of $7 million a year, far more than the $1 million average paid to presidents of major public universities.

In addition, student loans in the private sector – as distinct from federal loans – are traded on the investment market often creating a cloudy paperwork trail as to who owns the loans and deserves the monthly payments, much as happened in the sub-prime mortgage market nearly a decade ago By mid-2017, as many as $5 billion worth of these private loans were being disqualified by courts because they lacked adequate paperwork, meaning that tens of thousands of former students may get their debts wiped off, especially on loans to students who attended for-profit colleges.

“On the Hook to Wall Street”

“On the Hook to Wall Street”

By far the largest for-profit university and the largest recipient of taxpayer subsidies – $3.4 billion in fiscal 2012 – is the University of Phoenix (enrollment 470,000 in 2009). Between 2009 and 2013, it received nearly $1 billion in tuition assistance for Iraq and Afghan veterans. One study found that it spent as much as $600 million a year on advertising.

But richly funded as it was, the University of Phoenix has compiled a graduation rate of under 15%, a student withdrawal rate of over 60%, and more than one in four of students’ defaulting on their loans within three years of leaving school, according to the Education Department.

Before retiring in 2014, Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa, long-time chair of the Senate Education Committee, observed that the University of Phoenix began reasonably “as a college completion school.” But since 1994, when it became a publicly traded corporation, Harkin asserted, “They’re on the hook to Wall Street. I think what really turned this company is when they started going to Wall Street, started raising hedge fund money, and then they had to meet quarterly reports, and all they were interested in, basically, was ’How much money are ya makin’?”

Ripe for Regulation

The Iowa Democrat questioned whether large corporations whose primary mission is to make profits for investors and to boost their stock price on Wall Street can be entrusted to give top priority to the needs of its students.

Speaking of for-profit universities, Harkin said: “This is an industry that is ripe for, begging for, regulation. The bottom line is that a large share of the $32 billion that taxpayers invested in (for-profit) schools in 2010 was squandered. And this cannot be allowed to continue.”

Progress Report Success Story Additional Readings Organizations

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.