Gerrymandering:

Gerrymandering:

Rigging Elections by Stacking the Map

Gerrymandering:

Gerrymandering:Rigging Elections by Stacking the Map

How Gerrymandering Distorts Elections

In a prophetic column in early 2010, Republican strategist and political guru Karl Rove asserted: “He who controls redistricting can control Congress,” and that is just what Rove had his eye on doing for the GOP.

The cunning manipulation of political district lines by Democrats or Republicans to guarantee their own election and protect their lock on power has a long and byzantine history in American politics. But the black art of gerrymandering is now being carried to extremes. And it is undermining the integrity of American elections.

For now, as never before, sophisticated modern mapping software such as Maptitude, RedAppl, and autoBound, enables party strategists to stack the deck by carving and slicing neighborhoods down to the precise block or household in order to ensure victory for their party.

In state after state, especially those with closed party primaries, gerrymandering distorts the overall popular vote, sometimes turning the results upside down. After the 2012 elections, for example, Congress did not accurately reflect the people’s votes.

Democratic candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives outpolled Republican candidates nationwide by roughly 1.4 million votes. But Republicans emerged with a 33-seat majority in the House, capitalizing on the crafty GOP gerrymandering devised by Rove and others.

Independents Are Robbed of Their Vote

So gerrymandering can and does rig partisan outcomes. But the most malignant effect of gerrymandering and party primaries is to disenfranchise tens of millions of independent voters, now roughly 40% of the U.S. electorate – more than in either major party.

In most districts of populous states, independents and members of the minority party are quite literally robbed of any meaningful vote for the US House of Representatives in election after election because they cannot vote in political party primaries. This is where the crucial election decision is often made, and without Voting Rights, these groups are effectively shut out of the process. This undemocratic system needs to be changed so that everyone’s voice can be heard.

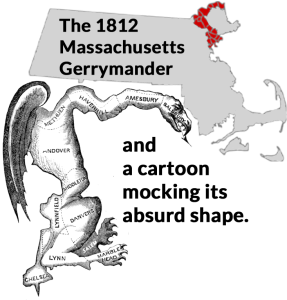

Take Massachusetts, where American gerrymandering was born. In fact, we get the name gerrymandering from the salamander shape of one district as they stacked the district maps in 1812. Two centuries later, the Democrats still gerrymander the district lines in Massachusetts even though 62% of the state’s electorate are either registered Republicans or Independents.

Because Democrats doctor Congressional district maps to insure Democratic winners, the Democratic Party primary in Massachusetts de facto becomes the decisive election for the House. But the 62% get no vote in the Democratic primary and their votes in the general election don’t matter because gerrymandering has pre-cooked the outcome and deprived them of any real say in that election.

REDMAP – The GOP’s Secret Plan:

But if Democrats rule the roost in Massachusetts and a few other states like Maryland, Connecticut, and Illinois, Republicans are the national champions of the modern gerrymander.

The key to their supremacy – and their control of the House of Representatives -is REDMAP, a secret plan devised by the GOP after Barack Obama won the White House in 2008. Nursing their wounds, Republican strategists like Karl Rove and Republican National Chairman Ed Gillespie set their sights on Congress. They devised REDMAP, a nationwide strategy that, Rove bragged, would spring a surprise on Democrats in the 2010 election.

Karl Rove

With $30 million in funds from corporations like Wal-Mart, tobacco giants Altria and Reynolds, and from Rove’s SuperPAC, American Crossroads, the GOP mounted a targeted drive to capture control of as many state legislatures as possible in the 2010 election in order to dominate congressional redistricting after the 2010 census.

GOP Victory Margin – 19 ‘Extra Seats’ in 7 States

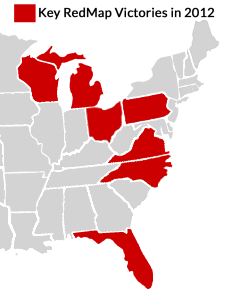

REDMAP was a smashing success. Republicans gained 675 legislative seats nationwide. That gave the GOP control of legislatures in states that held 40% of all House seats, versus Democrats, with only 10%. (The rest were under split control.)

Then came the GOP gerrymander crunch, creating safe seats for Republicans and severely limiting Democratic chances of victory by packing masses of Democratic voters into a few urban districts that Republicans knew were hopeless for the GOP anyway.

REDMAP worked beautifully. The Democrats won more popular votes in House elections nationwide in 2012, but the GOP walked away with a 33-seat House majority. Seven states held the key – Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

REDMAP worked beautifully. The Democrats won more popular votes in House elections nationwide in 2012, but the GOP walked away with a 33-seat House majority. Seven states held the key – Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

In those seven states, GOP House candidates narrowly outpolled the Democrats, 16.7 million to 16.4 million. There were 107 House seats at stake and so the GOP share of the popular vote should have entitled them to 54 seats vs. 53 for the Democrats.

But with their computer-powered gerrymandering, Republicans garnered 73 seats to just 34 for the Democrats. They won 19 extra seats – 19 seats beyond their share of the popular vote. Those seats gave Republicans a House majority in 2013. Without them, President Obama would have had a Democratic Congress to work with.

The Big Sort” vs Gerrymandering

Some political scientists dispute the impact of political gerrymandering. They contend that it is ethnic and social geography – where people like to live – and not gerrymandering that skews election results. In his book The Big Sort, journalist Bill Bishop wrote that Americans live increasingly in areas with people like themselves. Democrats pack into high-density urban areas and Republicans gravitate to the suburbs, small towns, and the wide, open spaces.

Because Democratic candidates win unnecessarily large super-majorities in their urban districts, Democrats waste votes, so the argument goes. According to this logic, the Democrats’ overall popular vote winds up under-represented, while Republicans, being more spread out, get overrepresented.

It is certainly true that for more than a century, waves of immigrant Americans have settled in ethnic conclaves near like-minded and like-cultured neighbors and people have gravitated toward others of their economic or social status. But that’s not new in America. It predates the civil war.

Flip Flops in Texas and North Carolina

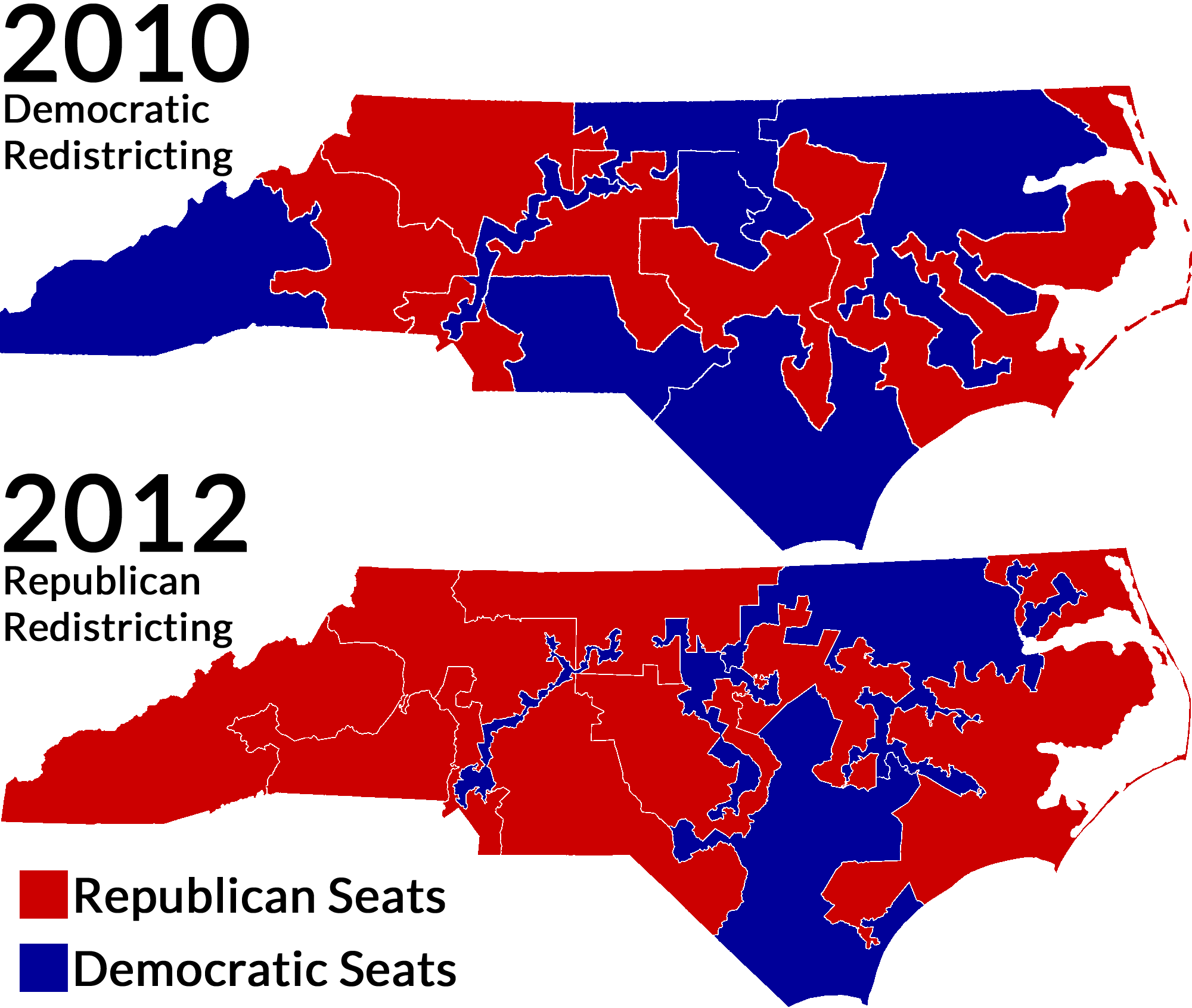

What the Big Sort analysis ignores is the dramatic shifts that occur after party control of a state changes hands. Before REDMAP, Democrats in North Carolina carried the popular vote for Congress and won a 7-6 majority in the state’s House delegation in the 2010 election, under the redistricting plan drafted by Democrats in 2001.

Two years later, in 2012, Democratic House candidates again won a statewide popular vote majority for the House. But a new gerrymandered map had been drawn by the Republican-dominated legislature, and Republicans emerged with 9 seats to 4 for the Democrats. A miraculous switch of three seats with little change in population.

Two years later, in 2012, Democratic House candidates again won a statewide popular vote majority for the House. But a new gerrymandered map had been drawn by the Republican-dominated legislature, and Republicans emerged with 9 seats to 4 for the Democrats. A miraculous switch of three seats with little change in population.

Karl Rove has a fistful of examples to show how gerrymandering swings elections. Promoting REDMAP to Republican funders, Rove trumpeted the GOP triumph in Texas after the special redistricting done when the GOP won control of the state legislature in 2002.

Back in 2001, Democrats had drafted a redistricting plan that gave them a 17-15 edge in the Texas delegation to the 107th Congress. But in 2004, after Republicans had engineered an unprecedented second redistricting, the GOP came out on top by 21-11 – a net switch of 6 seats, the harvest of gerrymandering not the Big Sort.

The 2016 Election for the House – Over Before It Starts

If political competition and voter choice are the bedrock of American democracy, gerrymandering is alien distortion. A core idea of the gerrymander is to create local political monopolies that literally leech serious competition out of all but a tiny fraction of House elections – and most state legislative elections.

So efficient and pervasive has modern gerrymandering become that more than a year before anyone casts a ballot in November 2016, a savvy political reporter could predict the outcome of nearly 90 % of races for the House of Representatives. So the contest is over before it begins.

In fact, that was exactly the conclusion of Charlie Cook, one of the nation’s premier election reporters and analysts and founder of The Cook Political Report. Eighteen months before the 2016 elections, Cook commented: “The Democrats could win every single competitive race in the country (in 2016) and still come up short and not pick up 30 seats they need for a majority.”

Gerrymandering Squeezes out the Political Middle

A major victim of partisan gerrymanders and closed party primaries is the moderate middle – moderate voters and centrist politicians willing to work with the other side. Moderates and centrists get squeezed out by gerrymandering. Southern Republicans manipulated district maps to kill off conservative southern Democrats and northern Democrats did the same to moderate House Republicans in the Northeast.

This system has accelerated the rise to power of extremists. This happens largely because in most gerrymandered districts, primary elections have become more decisive than the general election, and in primaries, the de facto power of decision rests with the party faithful.

Typically, primary turnout is low, sometimes extremely low. In the 2014 mid-term elections, Republican primary turnout nationwide was 8.9% of the electorate; for Democrats, it was 14.5%. In seven state primaries, turnout fell below 4%. Such tiny turnouts give enormous leverage to hardcore partisan voters, well-funded special interest groups, and more extreme, ideological candidates

Because primary voters often differ significantly in the views from average voters, there is often a disconnect between the broad electorate and the politicians who win primaries and get elected. In recent years, the widespread victories of partisan extremists fuel gridlock in Washington.

“The combination of closed party primaries, gerrymandering of districts and money – that’s why the system is broken,” says eight-term, former Oklahoma Republican Congressman Mickey Edwards. “This problem is deep, deep. The political system is more and more disconnected from the country. We have a system where what the majority of the voters might prefer doesn’t matter because the parties control the process, the parties limit their choices.”

The Push for Reform

The pernicious effects of gerrymandering and closed party primaries and their stepchild, the endless partisan warfare in Washington, have spawned a populist backlash, a sharp and growing chorus of protests at the grassroots. Citizen activists are pressing for reforms to restore the primacy of voters, create a more level and open playing field, and to ensure a fair outcome in American elections by throwing out the politically corrupt practice of partisan gerrymandering.

Over the last decade or more, half a dozen states have ejected political officeholders with their own self-interests from responsibility for drawing the maps for congressional districts. They have turned over that critical task to nonpartisan citizens commissions.

In half a dozen other states, public interest groups like Common Cause and the League of Women Voters have filed lawsuits challenging the legality and constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering. And lately, the courts have given encouragement to reformers by endorsing the interests of citizens exercising direct democracy against the political parties and partisan legislatures.

Progress Report Success Story Additional Readings Organizations

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.