Public Funding of Elections:

Public Funding of Elections:

Empowering Small Donors

Public Funding of Elections:

Public Funding of Elections:Empowering Small Donors

Teddy Roosevelt Sounds the Alarm

It’s an old and chronic cancer, dating back to the brawling campaigns and political machines of Tammany Hall and the Robber Baron era in the 1880s and 1890s – special interest money bankrolling American political campaigns.

In fact, President Theodore Roosevelt can lay claim to being the Paul Revere for American campaign reform. In the early 1900s, the rough-riding, trust-busting Republican President sounded the alarm over what he saw as the corrupting impact on American democracy of candidates’ and parties’ receiving private, fat-cat donations from Wall Street financiers, railroad barons, and oil tycoons.

“There is no enemy of free government more dangerous and none so insidious as the corruption of the electorate,” Roosevelt declared. The cure he prescribed was “the enactment of a law directed against bribery and corruption in federal elections.”

“There is no enemy of free government more dangerous and none so insidious as the corruption of the electorate,” Roosevelt declared. The cure he prescribed was “the enactment of a law directed against bribery and corruption in federal elections.”

In the Progressive Era, the public became so wary of private influence peddling through financing campaigns that William Howard Taft, the Republican nominee in 1908, turned down a $50,000 donation – equal to more than $1 million today. Taft feared that accepting such a large sum from one donor would make it look as though he’d been politically bought.

For Six Election Cycles, Public Funding Works

Congress enacted various reforms during the early 1900s, but it was not until 1971 that reformers came up with an alternative to private campaign money. The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 not only required candidates for federal office to disclose their funders and set limits on their spending, but also for the first time provided public funding of elections for presidential campaigns, though not for Congressional races.

The idea was to match funds raised by the candidates themselves with public monies – provided that the candidates agreed to spending limits. The public funds came from voluntary contributions by individual taxpayers through a check-off on their income tax returns, designating a small donation to public campaign funding.

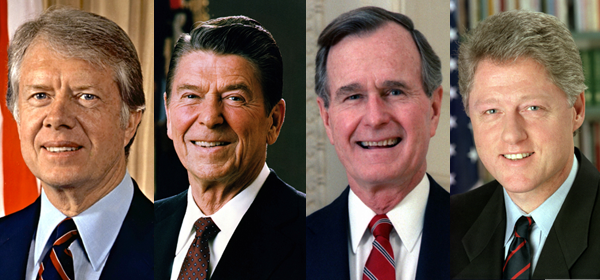

For six electoral cycles, from 1976 to 1996, public financing worked well for the campaigns of Presidents Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton, and their opponents. Availability of public financing encouraged transparency in campaign funding and sharply reduced the influence of wealthy donors.

For six electoral cycles, from 1976 to 1996, public financing worked well for the campaigns of Presidents Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton, and their opponents. Availability of public financing encouraged transparency in campaign funding and sharply reduced the influence of wealthy donors.

Many political observers credit the public funding system with giving voters a wider choice of candidates, including two underdogs who went on to win the Oval Office – Jimmy Carter in 1976 and Ronald Reagan in 1980. So public funding worked well in presidential races for a quarter of a century.

How the Public Funding Broke Down:

But the presidential public financing system began to fray during the 2000 campaign. Republican George W. Bush became the first nominee of either major party to pass up public matching funds during the primaries and to rely solely on money raised by his own campaign.

In the general election, however, Bush accepted public funds, as did his Democratic opponent, Al Gore. In 2004, https://www.careddi.com/ President Bush and his Democratic opponent, Senator John Kerry, both declined public matching funds during their party primaries but accepted public funding in the general election.

It was Democrat Barack Obama in 2008 who became the first nominee of either major party to break away entirely from using public funds for both the primaries and the general election. His Republican opponent, Senator John McCain of Arizona, followed the Bush-Kerry pattern, using public funds in the general election.

It was Democrat Barack Obama in 2008 who became the first nominee of either major party to break away entirely from using public funds for both the primaries and the general election. His Republican opponent, Senator John McCain of Arizona, followed the Bush-Kerry pattern, using public funds in the general election.

But Obama’s decision to opt-out was the death knell for the system. Since 2008, no presidential candidates have used the public financing system at all.

Why Public Funding Broke Down

The system broke down because the old arithmetic of public funding no longer fit reality. The sheer cost of running for president has risen astronomically since 1976, outstripping the amount of available public funding, in part because Congress never established a mechanism to index available public financing to the inflation in campaign costs.

An even more basic problem was the sharp decline in taxpayer participation in funding the system – from 30% in 1980 to 9% in 2008, meaning that less money was in the government coffers to fund campaigns. For the 2012 general election, the tax return check-off generated only about $80 million, a tiny fraction of the $2.3 billion actually spent on the 2012 presidential campaign.

Finally, the rise of independent campaign expenditures by SuperPACs permitted to operate without limits by Supreme Court rulings, created a huge disadvantage for any candidate who agreed to abide by campaign spending limits in order to qualify for public funding.

Today, more than $300 million of public funds earmarked for campaigns sits unused because candidates refuse to accept spending limits required to qualify for public funds. Former President Jimmy Carter has urged reviving that system. “I’d like to see public funds used for all elections — Congress, U.S. Senate, governor, and president,” said Carter. In Congress, Rep. David Price (D-NC) has proposed modernizing the system to catch up with today’s far higher campaign costs, but Republicans staunchly oppose it.

Public Funding Closer to Home – States and Cities

Public Funding Closer to Home – States and Cities

Yet while public funding of presidential campaigns has faded, public funding programs have achieved some notable successes at the state and city level since the late 1990s. States, as varied as Arizona, Connecticut, Maine, and Minnesota and cities such as Los Angeles and New York, have developed effective systems of public funding.

Some seek to empower small donors and to reduce the influence of billionaire and corporate donors, by providing matching funds at a high 6-to-1 ratio for small donations up to $175. The idea is to give candidates a strong incentive to go after small donors.

Two other ways of empowering small donors are giving them a tax credit for limited donations (up to $100, for example) or else giving all voters a small publicly funded voucher ($50 or $100), which voters can then donate to candidates of their choice.

An alternative strategy is to adopt Clean Elections reforms aimed at fostering a statewide culture of limited campaign spending and of spurning outside money. Under such a system, states or cities require candidates, whether for governor, mayor, legislature or city council, to qualify for public funding by raising a set number of small donations to prove they are viable candidates. Once candidates qualify and apply for public funding, they must agree to forego any further fundraising on their own. These systems work to keep campaign costs down and eliminate obligations to lobbyists.

The New Push for Public Funding

The recent explosion of MegaMoney in American campaigns – presidential races costing in the billions, individual Senate races topping $100 million – has reignited public concern about the excessive influence of fat-cat Mega Donors.

In Congress, there has been a rebirth of interest in public funding of campaigns to offset the impact of wealthy or corporate interests flush with cash and to give more clout to small donors. Several proposed bills incorporate reform strategies already working at the state or city level.

The reform measure with the broadest support is the Government by the People Act, first sponsored by Rep. John Sarbanes, a Maryland Democrat. This bill provides matching funds for donations up to $200 on a 6-to-1 ratio, as well as a $25 refundable tax credit for donations up to $200. It has attracted 155 co-sponsors – 154 Democrats plus Republican Congressman Walter Jones of North Carolina. But so far, the House Republican majority has blocked it from coming to a vote on the House floor.

The reform measure with the broadest support is the Government by the People Act, first sponsored by Rep. John Sarbanes, a Maryland Democrat. This bill provides matching funds for donations up to $200 on a 6-to-1 ratio, as well as a $25 refundable tax credit for donations up to $200. It has attracted 155 co-sponsors – 154 Democrats plus Republican Congressman Walter Jones of North Carolina. But so far, the House Republican majority has blocked it from coming to a vote on the House floor.

Empowering Small Donors, Engaging the Young

Public matching funds for small donors, Congressman Sarbanes argues, are a way to give some leverage back to average voters “Americans want to see Congress putting their priorities first, but the problem is that Big Money gets in the way,” he says, pointing to the campaign funding and influence of oil companies, Wall Street banks, and U.S. multinationals.

Like many others in public life, Sarbanes worries about the alienation of young people who are disenchanted with money-dominated politics. To him, public funding is an antidote. “It can be very motivating in terms of getting them involved again in the political process,” Says Sarbanes.

In the U.S. Senate, Illinois Democrat Dick Durbin has proposed the Fair Elections Now Act that creates a small donor matching system of public funding for both Senate and House candidates. Durbin’s bill, co-sponsored by 17 Democrats, provides a 6-1 match for small contributions up to $200 but no refundable tax credit. “This bill,” says Durbin, “will give candidates the opportunity to focus on dealing with our nation’s problems, not on chasing after campaign cash.”

In recent years, some members of the Republican Party in Congress have begun to support the use of taxpayer money to fund election campaigns. One proposal, called the CIVIC Act (Citizens Involvement in Campaigns), would offer tax credits for donations up to $200. The bill’s author, Wisconsin Representative Tom Petri, argues that this would help increase citizen involvement in the political process. However, other Republicans remain opposed to using public funds for election campaigns, and the CIVIC Act has not yet been passed into law. Voting rights are a key issue in American politics, and it is unclear how the debate over campaign finance reform will affect these rights in the future.

“Most would agree that the ideal way to finance a campaign is through a broad base of donors,” Petri observes. “Unfortunately, most Americans aren’t in the position to donate hundreds or thousands of dollars—but they want to get involved. We should be encouraging political participation.”

Progress Report Success Story Additional Readings Organizations

More Resources to Help You Empower Voters – Public Campaign Funding

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.