Dark Money:

Dark Money:

Outing Donors State by State

Dark Money:

Dark Money:Outing Donors State by State

The Push to Get Dark Money Out in the Open

The Supreme Court, in its rulings, has openly invited Congress and the American people to declare war on secret money in political campaigns – to pass laws and write rules that force dark money out into the open and ensure transparency in American election campaigns.

There are ample opportunities in the American political system for the public to demand full disclosure and put pressure on Congress and federal agencies to expose dark money.

The push is already underway in several arenas, blessed tacitly by decisions of the Supreme Court, from the 1976 Buckley v Valeo case to the 2010 decision in Citizens United, that it is constitutional for Congress and the states to require disclosure of campaign funding and spending.

With full disclosure, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in Citizens United, shareholders can determine whether their corporation’s political speech advances the corporation’s interest in making profits, and citizens can see whether elected officials are in the pocket of so-called money interests.”

Drying Up Rivers of Money

Drying Up Rivers of Money

Full disclosure is what most of the voting public wants, right, center, and left. Opinion polls show that the public favors clear rules and a level playing field. In one poll, nearly two-thirds wanted disclosure on political funding and spending – 66% of Democrats, 62% of independents, and 61% of Republicans.

The critical question is whether average Americans feel strongly enough about the dangers of dark money to organize and mobilize at the grassroots to force change at the state level and in Congress and at federal regulatory agencies.

If the public acts, campaign experts predict that genuine, sweeping disclosure laws would have a significant impact, drying up major rivers of MegaMoney flowing into elections because many big donors, whether corporations or individuals, seek anonymity. Openly backing controversial candidates can be bad for business. It risks offending customers and shareholders. If forced out of the shadows, many such funders, experts say, would stop funding or cut back.

In Congress, the D-I-S-C-L-O-S-E Act

The first to pick up on Justice Kennedy’s challenge to create a system of “effective disclosure ” were Democrats in Congress pushing for a new disclosure law before the 2010 mid-term elections. Rep Chris Van Hollen of Maryland and Senator Chuck Schumer of New York introduced what they called the D-I-S-C-L-O-S-E Act (Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light on Elections).

Delaware Republican Rep. Mike Castle joined Van Hollen in a bipartisan op-ed in The Washington Post, headlined “The Disclose Act Is a Matter of Campaign Honesty.” This bill, they said, “prevents special interests from hiding behind third-party groups, sham organizations, and dummy corporations by requiring the heads of organizations to ’stand by their ad’ the same way political candidates must take personal responsibility for their ads.”

That bill specifically required 501C nonprofits and all other outside groups spending $10,000 or more on election-related activities to disclose within 24 hours any donor who has given more than $10,000 to the organization. The law also required disclosure of transfers between organizations, if related to campaign spending.

The highwater mark came on June 24, 2010, when reform advocates overcame the opposition of then-House Minority Leader John Boehner and won a majority vote of 216-209 in favor of transparency in the funding of American elections.

Disclosure Misses by One Vote

In the Senate, the DISCLOSE Act ran into down-the-line Republican opposition spearheaded by Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, a long-time foe of campaign reforms. McConnell accused Democrats of drafting the bill behind closed doors and mobilized a Republican filibuster to block the Disclose Act from being put on the Senate calendar.

On the crucial procedural vote deciding whether the bill should go to the floor for debate and a vote, all 59 Democrats voted to end the procedural filibuster and 39 Republicans lined up solidly in opposition, leaving the bill one vote short of being sent to the floor, where its backers had a solid majority.

In 2012, the Disclose Act came up for two more Senate procedural votes, but Republican filibusters and solid opposition blocked the bill.

Pressing the FEC, SEC, and IRS to Take Action

With Congress deadlocked, campaign reform advocates have pressed for action by regulatory agencies such as the Federal Election Commission, the Securities Exchange Commission, and the Internal Revenue Service. Even without new laws, each agency has the power to require significant new campaign funding disclosures. Some groups have called on President Obama to issue an executive order requiring companies with government contracts to reveal their campaign donations.

More than a million people have signed petitions demanding that the SEC issue new rules mandating that corporations disclose their political spending to their shareholders. Some shareholder groups have shown up at corporate annual meetings demanding – and in some cases winning – shareholder votes calling for disclosure of political spending by their companies.

More than a million people have signed petitions demanding that the SEC issue new rules mandating that corporations disclose their political spending to their shareholders. Some shareholder groups have shown up at corporate annual meetings demanding – and in some cases winning – shareholder votes calling for disclosure of political spending by their companies.

Despite heavy fire from Congressional Republicans, the Internal Revenue Service proposed in November 2013 to tighten rules on “social welfare” groups, suggesting that their continued tax-exempt status depends on greater openness about their heretofore covert forays into political campaigns. But corporate interests and wealthy donors pushed Congress to block action by regulatory agencies and the new regulations were put on hold.

The Federal Election Commission is under steady pressure from election watchdog groups to tighten its standards and to enforce laws already on the books. But for a decade or more, partisan deadlocked between the three Republican and three Democratic Commissioners has paralyzed the FEC. with the GOP side repeatedly blocking enforcement. As the new rotating FEC chair in 2015, Ann Ravel, who had scored significant gains on funding disclosure in California as head of that state’s election watchdog agency, pushed for action. But after several months, she vented her frustration. “People think the FEC is dysfunctional, it’s worse than dysfunctional,” she fumed, saying that some commissioners were not even on speaking terms.

Will the FEC Crack Down on LLCs Channeling Masked Money?

But the 2016 campaign wrinkle that may spark an unusual bipartisan agreement for FEC action is the rising use of Limited Liability Corporations (LLCs) popping into existence for apparently no other reason than to mask the donors of $500,000 and $1 million donations to SuperPACs backing Republican contenders Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, John Kasich, and Jeb Bush, and Democrat Hillary Clinton, and many other political candidates.

In one case, an LLC named DC First Holdings donated $1 million to Jersey City’s Democratic Mayor Steven Fulop on its second day in business. “That, to me, is a red flag,” said Paul Ryan of the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center, “because it is unlikely that this business entity could have generated $1 million of its own revenue in a day.” In another case, Brooklyn investor Andrew Duncan funneled $500,000 to a pro-Rubio PAC through IGX LLC and admitted to the Associated Press that he had used the ghost corporation to avoid possible reprisals. These and dozens of other cases were cited in complaints to the FEC by watchdog groups like the Campaign Legal Center, Democracy 21, the Sunlight Foundation, and the Center for Public Integrity.

In one case, an LLC named DC First Holdings donated $1 million to Jersey City’s Democratic Mayor Steven Fulop on its second day in business. “That, to me, is a red flag,” said Paul Ryan of the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center, “because it is unlikely that this business entity could have generated $1 million of its own revenue in a day.” In another case, Brooklyn investor Andrew Duncan funneled $500,000 to a pro-Rubio PAC through IGX LLC and admitted to the Associated Press that he had used the ghost corporation to avoid possible reprisals. These and dozens of other cases were cited in complaints to the FEC by watchdog groups like the Campaign Legal Center, Democracy 21, the Sunlight Foundation, and the Center for Public Integrity.

Suddenly, after long resisting a crackdown on LLCs, the three Republican FEC commissioners came out strongly against the masking of the true campaign donors through shell companies, joining the three Democrats. “Six commissioners have now taken the position that closely held LLCs can violate the law under certain circumstances when they make contributions to super PACS,” said Republican Lee Goodman. “Now everyone should be on notice. If you funnel money through an LLC entity for the purpose of making a political contribution and avoiding disclosure of yourself, that is an abuse of the LLC vehicle.”

Crossfire at the SEC

The first shot in this battle was fired in August 2011, when ten legal experts on corporate governance at major universities filed a collective petition calling on the Securities and Exchange Commission to require corporations to disclose their political spending to shareholders. Citing earlier SEC rulings as precedents, they pointed to rising demands from the investing public for political transparency and asserted that disclosure was “necessary for corporate accountability.”

In 2011 alone, they noted, 25 of 100 major U. S. companies faced shareholder demands for proxy votes on campaign funding disclosure. “The level of shareholder interest in this area has been quite high, not just during the most recent proxy season, but throughout the past five years,” their petition asserted.

After the SEC put the issue on its agenda for 2013, Congressional Republicans set out to block SEC action. At a hearing in May 2013, House Republicans repeatedly warned SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White against adopting any rule on corporate disclosure. New Jersey Republican Scott Garrett hounded White “to make a clear and emphatic statement” that the SEC would not force corporations to disclose their campaign spending. A few months later, White and the SEC dropped the disclosure rule from the SEC’s agenda.

Pressures on Corporate America

But such groups as the nonprofit Center for Political Accountability kept up the drumbeat for reform. Public pressures for SEC action continued to mount. “The case for transparency in this area is clear and compelling to a broad spectrum of people,” observed Harvard law professor Lucien Bebchuk.

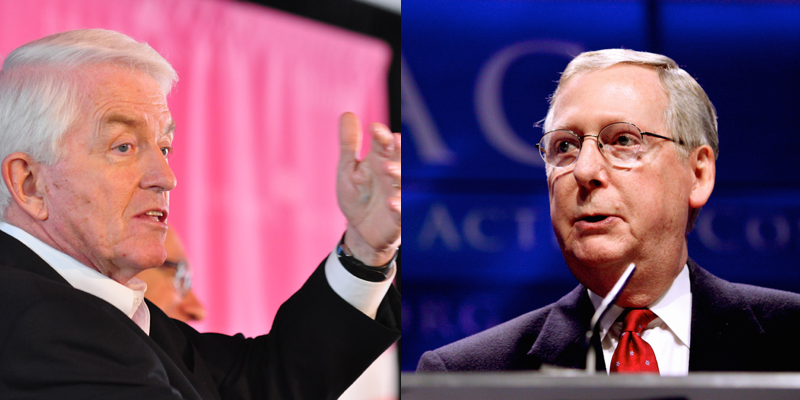

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, one of the largest dark money spenders in recent campaigns, strenuously objected. The disclosure proposals, thundered Chamber President Tom Donahue, were an attempt to silence Corporate America and stop business from promoting its interests through politics. In fact, however, petitions to the SEC did not seek to stop corporate political spending – only require such spending to be publicly disclosed.

At corporate shareholder meetings, the pressure for openness on campaign donations persists. In 2014, a majority of shareholders at Fannie Mae, Lorillard, Valery Energy, Dean Foods, and Smith & Wesson voted for transparency on corporate political spending on campaigns and political lobbying. Already, 60 companies have agreed voluntarily to make some disclosures, evidence that corporate disclosure can work.

US Chamber of Commerce President Tom Donahue (left) and Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (right). Images (CC),The Aspen Institute, and Gage Skidmore

Corporate America Strikes Back

But in December 2015, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and its political allies on Capitol Hill such as Senate Majority Leader Mitch Mcconnel, a staunch foe of campaign reform, struck back hard to block any governmental action to expose dark money.

Hidden deep in the $1.1 trillion omnibus spending bill passed on Dec. 18, they inserted a terse but blunt ban against any SEC action to force corporate dark money campaign contributions into the open. Section 707 declared that no funds “shall be used by the Securities and Exchange Commission to finalize, issue, or implement any rule, regulation, or order regarding the disclosure of political contributions, contributions to tax-exempt organizations, or dues paid to trade associations.”

And in a counterattack against public calls for the Obama Administration to issue orders requiring disclosure of political spending by government contractors, the Republican-controlled Congress fashioned Section 735, a provision that bars any government agency funded by the spending bill from requiring disclosure of campaign spending by government contractors. A third provision, Section 127, blocks the Internal Revenue Service from using appropriated funds to issue rules that would clarify and define what constitutes “political activities” by so-called non-profit “social welfare” organizations.

Reformers Ask the IRS to Close Loopholes

Since 2010, the IRS has been a flashpoint in the battle over dark money – accused by Congressional Republicans of biased and dictatorial tactics toward conservative groups. But it has also castigated by reform-minded Senators like Rhode Island Democrat Sheldon Whitehouse as “toothless” – too vague in its rules and too lax in enforcement. Reformers want the I.R.S. to close legal loopholes that protect dark money.

“The IRS must enforce the tax laws to prevent groups from improperly claiming tax-exempt status as section 501 (c ) 4 ‘social welfare’ organizations,” Fred Werthemier, head of the pro-reform group Democracy 21, wrote. “These groups have misused the tax code to deny citizens basic information … about the donors financing campaign expenditures to influence their votes.”

“The IRS must enforce the tax laws to prevent groups from improperly claiming tax-exempt status as section 501 (c ) 4 ‘social welfare’ organizations,” Fred Werthemier, head of the pro-reform group Democracy 21, wrote. “These groups have misused the tax code to deny citizens basic information … about the donors financing campaign expenditures to influence their votes.”

The I.R.S. is not tasked with enforcing campaign spending laws, but it sets rules for the tax-exempt status of non-profit groups. That includes determining whether such groups qualify for federal tax exemptions because they are working for the common good and “social welfare,” or whether their funding of political campaigns and political attack ads disqualifies them for tax-exempt status.

The Howl from Special Interest Groups

When Congress granted tax exemptions to charitable social organizations in 1913, it specified that they had to be “operated exclusively for the promotion of the social welfare.” In short, no politics. In recent years, the I.R.S. has reinterpreted that law more leniently, allowing 501 (c ) 4’s to do some political spending, but not to let politics become a majority of their activities. The problem was the I.R.S. did not define “political activities” or vigorously enforce the law.

Confronted by a mounting hemorrhage of dark money and rising public criticism of political spending by “social welfare’ non-profits, the I.R.S announced in November 2013 that it planned to spell out clearer rules on just how much political activity could legally be undertaken by 501 (c ) 4’s if they wanted to remain tax-exempt.

Its concerns were targeted at what it called “candidate-related political activities that do not promote social welfare,” such as advocating for or against candidates; contributing money and volunteer time to candidate campaigns; funding TV ads, or any other form of candidate messaging including mass mailings, websites and phone banks; “electioneering communications” close to election day; as well as voter registration and get-out-the-vote drives.

In response, the I.R.S. was inundated with more than 150,000 public comments. Special interest groups from left to right, from Planned Parenthood and the American Civil Liberties Union to Tea Party affiliates and the National Rifle Association, squawked that their civic engagement activities would be curtailed if they had to disclose their funders. Not actually true. Any new I.R.S. rules would only set the conditions for tax-exempt status; they would not curtail any activities.

But the prospect of reform set off another firestorm among politicians on Capitol Hill who feared the loss of some big-time campaign funders who did not want to be publicly identified. Under political pressure, the I.R.S. decided to move a bit more gingerly. In May 2014, the agency said it might modify its proposed rules but was still “committed to providing updated standards for tax-exemption that are fair, clear, and easier to administer.” Then in December 2015, the Republican-controlled Congress barred the IRS from using appropriated funds to issue any new rules designed to rein in political spending by non-profit groups.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin (CC) Treasury Photo

Since taking office the Trump Administration has buried the very idea of requiring disclosure of the political funding and spending by “social welfare” non-profits. In July 2018, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin added another layer of protection for wealthy dark money donors. Mnuchin made it harder for anyone to identify dark money donors by abolishing the I.R.S. requirement that tax-exempt groups had to disclose their main funders to the I.R.S., even if not to voters. In short, the I.R.S. was deliberately putting itself in the dark about the depth of dark money financing of campaigns by groups that were supposed to be promoting the “social welfare” and not playing politics.

When Washington’s Stuck,

States Take Action

When Washington gets paralyzed, state and local governments often move into the vacuum, and that has happened on campaign transparency. In the past few years, several states have adopted new laws or regulations to shed sunlight on campaign dark money and force secret donors out into the open.

As a tool for reform, the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center in Washington has drafted the American Anti-Corruption Act, which bans campaign donations by lobbyists and by businesses dealing with elected officials as well as promoting disclosure of campaign contributors. Represent.US, another nonpartisan reform group, has developed a Do-It-Yourself version of the American Anti-Corruption Act for grassroots organizations to use for achieving sunlight reforms at the state and city level.

Check this list to see which states are taking the lead for greater exposure of dark and special interest money in election campaigns:

Alaska:

- Aug. 29, 2017- A trans-partisan trio of reformers announce drive for popular referendum on a good government act that would reduce financial conflicts of interest for state lawmakers and bar “foreign influenced corporations” from spending money on campaigns that target individual candidates in Alaska. The reform ballot initiative is proposed by state representatives Jonathan Kreiss-Tomkins (D-Sitka) and Jason Grenn (I-Anchorage) and long-time Anchorage Republican activist Bonnie Jack. Their proposed Government Accountability Act, filed with the Lieutenant governor’s office, would bar lawmakers and aides from accepting meals or drinks bought by lobbyists, costing more than $15; require lawmakers to disclose conflicts of interest related to their jobs and family, and bar state payment for legislators’ foreign travel unless they previously file a public report showing how their trip would benefit the state of Alaska.

- Jan. 11, 2018 – Backers of a good government reform act aimed at curbing legislators’ conflicts of interest and barring foreign money from Alaskan political campaigns say they are submitting petitions with 45,000 signatures to the state Division of Elections – more than enough to put their reform measure on the 2018 ballot. Roughly 32,000 signatures are required for a ballot initiative in Alaska.

- May 11, 2018 – The Alaska Legislature, seeking to pre-empt a good government ballot initiative, passes House Bill 44, which contains several provisions of the ballot initiative, including tougher rules on lawmakers’ conflicts of interest and tight limits on how much lobbyists can spend on meals or drinks for lawmakers. The Alaska constitution empowers the Legislature to pre-empt a citizen-backed ballot initiative by passing a “substantially similar” measure, thereby precluding a popular vote. HB 44 contains several provisions similar to the ballot initiative, but it does not include the provision prohibiting foreign-influenced corporations from spending money to influence Alaska elections.

- June 1, 2018 – Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott rules that House Bill 44, passed by the legislature in May, is similar enough to the Government Accountability Act reform initiative to replace that ballot measure and preclude a popular vote on campaign finance reforms. One of the initiative’s sponsors, Rep. Jason Grenn (I-Anchorage), suggests the group may appeal the lieutenant governor’s ruling. “We have a responsibility to the 45,000 Alaskans who signed that petition to keep up our end of the bargain,” says Green.

- Nov 3, 2020- By a narrow majority, Alaska voters adopt an election reform package that includes a ban on dark money by requiring the disclosure of the true sources: of any p9litical campaign contribution of more than $2,000. The contributor is required to report donations to the state election authorities within 24 hours and disclose their name, address, occupation, and employer.

Arizona:

- Jan. 21, 2016 – Honest and Open Coalition, led by two former mayors of Phoenix, launches drive for new campaign disclosure amendment to state constitution that would require organizations, including tax-exempt nonprofits, to report (within 24 hours) “original sources” and “intermediaries” of all major contributions for any campaign expenditure exceeding $10,000 and intended to influence candidate elections. John Opdyke, president of Open Primaries, says his group has donated $1 million and will work to raise another $13 million to help expose dark money flowing into Arizona campaigns and to reform the state’s party primary system. Texas billionaire John Arnold is identified as the campaign’s primary donor.

- March 8, 2016 – In straight 18-10 party-line vote, Republican Senate majority passes SB 1516 reducing requirements for disclosure of funding sources for campaign advertising. legislation later passed by the Arizona House would kill authority of state election officials to subpoena candidate records, allow unlimited spending by outside groups on social media sites without disclosure and permit candidates to transfer donations made to them to other candidates, with the approval of donors.

- March 10, 2016- Texas billionaire John Arnold abruptly backs out of Arizona’s Open and Honest Elections movement, amid reports that Gov. Doug Ducey’s office pressured donors to withdraw support for citizens’ movement advocating an amendment to the Arizona constitution to expose anonymous dark money donors.

Amanda Pstross (L) has been leading the charge to make campaign fundraising more transparent after Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey (R) signed a bill protecting Dark Money. Photos (CC): Gage Skidmore, and Tracy O altered by Reclaim.

- March 30, 2016 – Gov. Doug Ducey signs Senate Bill 1516, which largely dismantles Arizona’s laws for exposing dark money campaign funding by canceling requirements for funding disclosure by non-profits, ending required reports on “in-kind” campaign contributions, and allowing candidates to pass on to other candidates donations made to them. Ducey, backed in his 2014 governor’s race by $1.3 million in dark money from the Koch network, hailed the bill as a step toward simplifying Arizona laws to provide “increased freedom of speech.” But critics, such as Republican political consultant Chuck Coughlin, called the new law a “dark money grab” that “creates colossal loopholes for contributors” to spend unlimited funds backing or attacking candidates and still remain anonymous.

- April 12, 2016 – New group, Arizonans for Clean and Accountable Elections, files proposed ballot initiative to revoke major elements of the SB 1516, the dark money protection bill signed by Governor Ducey. This initiative, supported by Every Voice, a national reform organization, and by former Democratic leaders in the state legislature, would reinstate disclosure by nonprofits, require corporations and independent groups spending at least $10,000 on elections to disclose donors of more than $1,000, require lobbyists to disclose their in-kind donations to lawmakers, and lower the limits on individual campaign donations by two-thirds. The group must gather 150,642 signatures by July 7 to put the issue on the November ballot.

- June 26, 2016- A grassroots petition drive for a ballot initiative to expand Arizona’s Clean Elections system with tougher campaign funding disclosure requirements and public funding for campaigns is called off, its leaders charging that “dirty tricks” by the Arizona Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Arizona Public Service had blocked it from collecting enough signatures to qualify for the ballot. The petition drive collected about 100,000 signatures, well short of the 150,000 needed. Every Voice, a national reform advocacy group and a major backer, said the Arizona reform effort got off to a slow start because one signature-gathering firm pulled out of its proposed contract at the last minute, hired away by opposition groups to work on sham initiative campaigns backed by wealthy business interests.

- Nov. 6, 2018- A whopping 85.2% of Phoenix voters pass a proposed city charter amendment that requires individuals and organizations to disclose campaign expenditures and any campaign donations of $1,000 or more in a Phoenix city election, whether for candidate or ballot measure. In a provision aimed at stopping rich donors from hiding behind the anonymity of political non-profit groups with vague names, the measure mandates disclosure of both the original and intermediary sources of major contributions.

Arkansas:

- Jan 23, 2014 – Arkansas Secretary of State certifies Campaign Finance and Lobbying Act of 2014 to go before Arkansas voters as referendum issue in November. Popularly known as an ethics reform bill placed on the ballot by the governor and state legislature, the proposed law calls for a ban on direct corporate contributions to candidates for the legislature, for governor, and other statewide offices. It put limits on financial gifts from lobbyists to elected state officials and bars former legislators from becoming a lobbyist for two years after leaving office.

- Nov. 6, 2014 – A ballot measure aimed at tightening ethics laws and changing term limits in Arkansas bucks expectations and passes with 52 percent majority vote. The measure, the Campaign Finance and Lobbying Act of 2014 bans lobbyist gifts to state officials, prohibits direct corporate and union contributions to candidates, and lengthens the time period before former lawmakers can become lobbyists (from one to two years).

California:

- May 2014 – California’s legislature breaks new ground by enacting a law that requires any organization that spends $50,000 in a California election to rapidly report all funding and spending. This is the first disclosure law in the nation that covers nonprofit social welfare groups as well as political committees. Until this law was passed, “social welfare” groups avoided disclosure by contending that their primary mission is not politics and so laws requiring disclosure by “political committees” do not apply to them. The California law erases the legal distinction between political committees and 501C’s. It treats them all as “multi-purpose” organizations and requires them all to report political expenditures and all donors.

- Sept. 2015 – A group led by Silicon Valley entrepreneur Jim Heerwagen announces a drive to pass a referendum, dubbed the Voter’s Right to Know Act, that would amend the state constitution with a provision that would require that the top “true donors” be listed on every political ad. It would also require modernizing California’s campaign finance disclosure database to make it easier to track special interests. If this act passes, California would become the first state to put the voter’s right to know about campaign funding on a legal par with fundamental guarantees for basic rights such as free speech and privacy. On Feb 8, 2016, the group notified the California Secretary of State that it had collected 25% of the 585,407 signatures needed to get their proposal on the ballot.

- Jan. 2016 – Wealthy Republican real estate attorney John Cox proposes taking transparency a giant step further – requiring California politicians to wear the corporate logos of their ten top campaign donors on their clothes, like race-car drivers. Cox, moving to put the issue before California voters in November 2016, pledged $1 million to help pay for gathering 376,880 signatures needed to qualify for the ballot.

- Jan. 27, 2016 – With a bipartisan supermajority vote of 60-15, the California State Assembly passes the California Disclose Act (AB 700. The act requires that all ads on radio, TV, and in print, mailings, robocalls and online that either support or oppose candidates or ballot measures, prominently disclose the three “top contributors” – individual donors contributing $50,000 or more to any group paying for the ads. Bill spells out rules to make disclosures easily readable – size, placement, minimum five seconds on 30-second TV ads, lettering in sharp contrast with background, all to ensure easy reading. After first reading in California Senate, the bill, which has been heavily promoted by the California Clean Money Campaign, is sent for action to Committee on Elections and Constitutional Amendments, where it was bottled up.

Responding to popular demand and legislative action, California Gov. Jerry Brown recently signed the California Disclose Act.

- Oct. 7, 2017 – After three years of legislative battling, Gov. Jerry Brown signs new political transparency law promising tighter rules to expose dark money in political campaigns and to bar major funders from hiding behind opaque and often misleading feel-good group names. Over the opposition of both corporations and labor unions, the state legislature passed the California Disclose Act (AB249) requiring that names of the three largest donors be shown on political ads for and against candidates and ballot measures in California in print large enough for voters to read easily.” No more fine print,” said the bill’s author, Assembly Speaker pro Tem Kevin Mullin. “California voters will now be able to make informed decisions, based on honest information about who the true funders are of campaign ads. ” The California Clean Money Campaign mobilized 350 organizations and gathered 100,000 signatures to petition the legislature for enactment. But the state’s political ethics watchdog agency, the California Fair Political Practices Commission, complained that the new measure would make it harder for the agency to prove some cases as well as reducing the fines that it can levy against violators.

Delaware:

- Aug. 15, 2012 – Gov. Jack Markell signs Delaware Elections Disclosure Act that tightens state laws to require independent expenditure groups that spend $500 or more on “electioneering communications” to disclose their funding sources within 24 hours. To stop groups and individuals from skirting previous disclosure requirements simply by not using trigger phrases like “Vote for Smith” or “Defeat Jones,” the new law requires funding disclosure (regardless of wording) for any ad that mentions a candidate’s name within 30 days of a primary or special election or within 60 days of a general election. In addition, the law requires identification of the “responsible party” of any organization that contributes more than $1,200 to a political party or a political action committee during a given election cycle.

- Oct. 23, 2013 – The Center for Competitive Politics files suit on behalf of Delaware Strong Families, a 501(c)3 group that regularly distributes voter guides before elections, charging that the disclosure law violates the group’s First and Fourteenth Amendment rights. “The law requires groups to choose between publishing a voter guide or submitting to substantial regulatory burdens while violating the privacy of even their small-dollar supporters,” said Allen Dickerson, CCP’s Legal Director.

- July 16, 2015 – U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals upholds constitutionality of Delaware Disclose Act, allowing state to enforce the law which had been temporarily enjoined by a lower court ruling. The appeals court rejects the argument that disclosure can apply only to “express advocacy” for a candidate, and asserts specifically that the law applies to the voter guide circulated by Delaware Strong Families. The court decision is hailed by Governor Markell as “an important victory for transparency in Delaware elections…in an era of increasing spending by outside interest groups who too often have been allowed to hide the sources of their revenues.”

Florida:

- May 17, 2016- Miami-Dade County commission voted 7-1 to enact ordinance requiring candidates for county commission or Mayor of Miami to disclose their ties to independent groups that raise funds on their behalf. Five current commissioners skipped the vote. Previously, local law did not require candidates to disclose their ties to political action committees raising funds on their behalf. The new ordinance, by requiring candidates to register when they help raise funds for independent political action committees, aligns local law with state requirements.

Idaho:

- April 6, 2015 – Republican Gov. C.L. “Butch” Otter signs law tightening disclosure requirements under Idaho’s Sunshine Law, passed by 77.6% majority vote in 1974 popular referendum. The new measure, passed unanimously by Republican-controlled state house and senate, requires any person or independent group, as well as candidates and parties, who spend more than $100 on electioneering communications with 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary, to report names of all donors of $50 or more at least seven days prior to any election. If $1,000 or more is spent on political ads or handbills in the last 16 days before an election, a disclosure report must be made within 48 hours. The law mandates that no contribution can be made indirectly through an intermediary so “as to conceal the identity of the source of the contribution.”

Holli Woodings, reform leader.

- May 2, 2016 – Keep Idaho Elections Accountable, a coalition seeking firmer controls on campaign finance, delivers petitions with 79,000 signatures (well over the required 48,000) calling for a popular referendum in November on a citizens initiative that would bar campaign donations to candidates of more than $50 by lobbyists or by major state contractors. The new measure, supported by the national reform group Every Voice, would mandate speedy reporting on funds spent on broadcast, print and other forms of political advertising within 24 hours of ads being placed. The initiative would also require disclosure of the occupation and employer as well as names and addresses of donors contributing $50 or more to candidates, parties, independent groups, or spending on electioneering communications. Former Idaho State Rep. Holli Woodings (D) of Boise, leads the campaign reform movement.

- July 1, 2016 – The grassroots reform petition drive by Keep Idaho Elections Accountable failed to qualify its campaign finance initiative for 2016 because it fell short of the number of verified signatures needed. A majority of the 75,000 petition signatures were automatically disqualified, officials said, because people had moved since they first registered to vote and their current address did not match their voter registration records. “The poison pill ended up being people who believed they are registered to vote, but they’ve moved,” said Holli Woodings, who led the reform campaign. Although ballot initiatives were common a few years ago, no proposed initiative has successfully managed to get on the Idaho ballot since 2013, when Idaho lawmakers drastically tightened legal requirements for ballot initiatives.

Maryland:

- April 2013 – Maryland legislature passes campaign disclosure law to require political nonprofits that claim 501 (c ) 4 status as well as other independent groups to report their election spending and their five largest donors if they spend more than $6,000 in a Maryland election. The law also applies to out-of-state groups that relay funds to political entities operating inside Maryland if this is done with “the express purpose” of funding an “electioneering communication.” Under the new law, state contractors doing more than $200,000 in business with state agencies are mandated to report their political contributions.

Massachusetts:

- Aug. 4, 2014 – Gov. Deval Patrick signs SuperPAC disclosure law passed by wide majorities in both houses of the Massachusetts legislature, seeking to expose deluge of corporate and labor money flooding into 2014 campaigns for state offices. Tightening up previous disclosure laws passed in 2009, new law immediately requires all groups making independent expenditures, widely known as super PACs, to disclose their donors within seven days, or within 24 hours of running ads if the ads are booked or run within 10 days of an election. Previously, independent expenditure groups had to report their campaign spending on ads within seven days, but donors were only reported after the election. Also, under the new law, television, print, and radio ads created by independent groups must list the names of the group’s top five donors in the ad, for any contributors who give $5,000 or more.

- Fall 2015 – To further tighten Massachusetts campaign disclosure laws, Democratic representative Josh Cutler introduces a bill requiring disclosure of funders by any group spending $250 or more on an “electioneering communication” within 90 days of a Massachusetts election, including groups not registered as political committees. Earlier laws had specified that to require disclosure, funds had to be “solicited” for campaign ads, a loophole that allowed groups to refuse disclosure on grounds that their funds were solicited for general purposes such as public education or lobbying. To close that loophole, the new bill simply requires disclosure of funders for money spent on political communications, regardless of how funds were raised. A second measure, sponsored by Rep. Garrett Bradley, the Democratic Majority Whip, requires a listing of the top five funders for direct mailings to voters and billboard ads as well as television, print, radio, and internet advertisements.

Minnesota:

- March 8, 2016 –Thirty-two of 61 Democratic members of Minnesota House introduce a bill calling for a popular referendum on a state constitutional amendment that would require disclosure of spending on political communications by any person or group, including political nonprofits, seeking to reach an audience beyond its own membership. A previous proposal in 2013 lacked leadership support and failed. This time the House Democratic minority leader Paul Thissen is among the co-sponsors and a similar bill is introduced in the Senate. Instead of codifying disclosure requirements, the proposal asks for a popular vote this November endorsing disclosure of all but “de minimus” spending on campaign communications that ”expressly advocate” for or against a candidate or “not susceptible to any other interpretation” if made “within reasonable proximity” to an election. To go on the November ballot, the measure requires a favorable vote from the legislature, where Republicans hold a 73-61 majority in the House while Democrats hold a 39-28 majority in the Senate.

- May 22, 2016 – Minnesota legislature ends its regular session without taking action on House and Senate bills for a constitutional amendment to require fuller disclosure of campaign funding and spending.

Missouri:

- Dec. 12, 2015 – State Sen Rob Schaaf, Republican from St. Joseph, introduces the Missouri Anti-Corruption Act, a bill to bar legislators from receiving funds or gifts from lobbyists; prohibit political contributions by corporations or unions; restore campaign funding limits abolished in 2008 by the Missouri legislature and require disclosure of all money spent on Missouri politics. Schaaf’s advocacy of reform represents 180-degree reversal of his vote in 2008 to abolish campaign spending limits. “At the time I believed it was the right thing to do, but subsequently I’ve come to realize that the benefits of campaign contribution limits outweigh the downside,” Schaaf told a news conference. “If somebody gives you a big check, the rule is that you dance with the one who ‘brung’ you. You are going to have a certain benevolent feeling toward them.”

- January 2016 – Missouri legislative leadership sends Schaaf’s bill for campaign finance reform to the Senate Rules Committee, where it is bottled up.

- Spring 2016 – A new group, Returning Government to the People, launches petition drive to put on November 2016 ballot a citizens initiative seeking to amend the state constitution to restore campaign funding limits abolished eight years ago by state legislature. Its leaders are two Republicans – State Sen. Rob Schaaf and Fred Sauer, a conservative who heads the anti-abortion group Roundtable for Life. Their proposal seeks a limit of $2,600 in personal donations to a candidate and a $25,000 limit on what a political party could donate to one candidate.

- Aug. 9, 2016 – Secretary of State Jason Kander certifies ballot initiative for an amendment to Missouri state constitution that would establish limits on campaign contributions to political parties, political committees, or committees to elect candidates for state or judicial office and prohibit individual candidates and political entities from intentionally concealing the source of campaign contributions. The measure has backing from high-profile Missouri Democrats such as Gov. Jay Nixon and U.S. Senator Claire McCaskill and a handful of Republican state legislators, though rival candidates for governor, Republican Lt. Gov. Peter Kinder and Democratic Attorney General Chris Koster have chosen to accept six or seven-figure donations.

- Nov. 8, 2016 – A 69.9% majority of Missourians vote in favor of an amendment to the state constitution that bars candidates and political entities from “intentionally concealing the source” of contributions to political campaigns and restoring ceilings on donations that had been revoked by the legislature in 2008. Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon joined several Republican legislators and a conservative funder in pushing for passage of campaign finance reforms. Nixon condemned the state’s uncontrolled system that permits “unlimited secret, dark money coming in out of these races – millions of dollars that nobody knows where it even is from, and then unlimited amounts for these small races – $50,000, $100,000 checks, $1 million, $2 million checks. That just corrodes confidence in democracy.” The measure, endorsed by 1,877,477 of nearly 2,7 million voters, will limit individual donations to candidates for state offices or judgeships at $2,600 and cap donations to political parties or political committees at $25,000.

Montana:

Montana Governor Steve Bull signs the Montana Disclose Act. He is joined by Sen. Duave Ankney (R-Colstrip) and Rep. Frank Garner (R-Kalispell). image: the Office of the Governor.

- Nov. 2015 – Montana legislature adopts broad campaign disclosure law requiring all groups, no matter their tax status, to disclose their sources of funds if they spend money on TV ads or other electioneering communications that mention a candidate or use a candidate’s image. Jonathan Motl, Commissioner of Political Practices, calls on voters to tip him off. “The people of Montana have to be vigilant,” Motl says. The state starts implementing the law on Jan 1, 2016. Critics fear that despite the effort at total disclosure, Montana law leaves a loophole for 501(c)4 nonprofits because commissioner, in order to require funding disclosures, must determine that a group’s “primary purpose” is to support or oppose political candidates or ballot issue

New York:

- 2013 – New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman issues regulation requiring nonprofits, including 501(c ) 4 organizations, “to report the percentage of their expenditures that go to federal, state and local electioneering.” Although this will increase the disclosures of political nonprofits, disclosure is required only once a year – after the election – and the rules lack specifics. Activist campaign reformers want Schneiderman’s rules clarified and put into law.

- Jan. 24, 2019 – In a move designed to expose campaign dark money, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signs law requiring that LLCs (limited liability corporations) identify all of their direct and indirect owners and their share of ownership. The new restriction was seen as a blow targeted at the real estate industry, which for two decades has used LLCs to pass anonymous donations to many state lawmakers to get them to block meaningful reform to New York City’s rent laws. The new law passed ten days ago by Democratic majorities in both houses of the state legislature, closes a loophole in campaign finance regulations opened by the state board of elections. In the future, it will subject LLCs to the same aggregate contribution limit of $5,000 that applies to other corporations and not let them set their own limits, as permitted by a state court decision.

New Mexico:

- Nov. 6, 2018 – By a whopping 75%-25% majority, New Mexico voters adopted a constitutional amendment to establish a seven-member state ethics commission to oversee ethical conduct by state officials, executive and legislative employees, candidates, government contractors, and lobbyists. The governor and legislative leaders of both parties would each name one commissioner and those five commissioners would select two more. No more than three could come from one political party.

- March 2019- Initial legislation passed by the New Mexico Senate to establish the duties and powers of the new state ethics commission did not include oversight reporting of campaign funding or campaign finance regulation, but focused largely on transparency in the operation of state agencies.

North Dakota:

- November 2018 -Taking their cue from grassroots citizen reformers in South Dakota who won a surprising upset victory in 2016, a coalition of civic groups in North Dakota mounted a petition drive in early 2018 to put anti-corruption reform on the November 2018 ballot, noting that North Dakota is one of only seven states without an ethics commission

- The coalition, led by the nonpartisan group North Dakotans for Public Integrity and the League of Women Voters, submitted petitions to state government calling for a constitutional reform measure to set up a state ethics commission and to ensure full online disclosure of election funding, restrictions on lobbyists gifts, a ban on foreign donations to state campaigns, no personal use by candidates of campaign donations, a two-year cooling-off period before state officials can become lobbyists, and strict conflict-of-interest rules for state agencies.

- By mid-July 2018, the grassroots reform movement had raised more than $400,000, some of it from national reform groups such as represent.us, that enabled it to collect 38,451 petition signatures, far more than the 26,904 valid signatures required to qualify their proposed anti-corruption amendment to the state constitution for a popular vote in November. On July 24, Secretary of State Al Jaeger certified the Anti-Corruption Amendment.

- State Republican leaders staunchly opposed the reform, arguing that North Dakota has no need for anti-corruption laws because state officials and lawmakers are already ethical. But reformers, including other Republicans, took issue. “It’s time to inject some transparency and accountability back into government here in North Dakota,” said Dina Butcher, Republican President of North Dakotans for Public Integrity. “Our aim is to ensure that government in North Dakota is working for you and your family, and for all North Dakotans. Passage of the North Dakota Anti-Corruption Amendment will affirm the North Dakota value that our government is for everybody – not just the wealthy, the well-connected, and the powerful. Who could disagree with that?:”

- When it came to a popular vote in November, the anti-corruption amendment won a solid 63.6% majority.

Oregon

- No 6, 2018 – In the city of Portland, an overwhelming 87% majority of voters approve an amendment to the city charter to force disclosure of campaign donors and require that TV ads name major funders. The citizen-led initiative, endorsed by the city council, also imposes a ban on corporate contributions in city elections and sets a $500 limit on individual campaign donations. To prod candidates for city office to focus more on average voters and less on big donors, the reform measure also offers a 6-1 public funding match for small campaign donations.

- Nov 3. 2020 – With a landslide majority, Oregon voters approve a constitutional amendment empowering the state legislature and local governments to impose limits on campaign contributions and spending and force disclosure of political dark money. Before this action, Oregon had some of the most permissive laws in American politics, with no required disclosure of campaign contributions or legally mandated caps on campaign spending. To fill that legal vacuum, the state legislature put on the ballot a constitutional amendment authorizing legal measures on campaign spending and it passed with more than a 75% popular vote majority.

Rhode Island:

- In June 2012, Gov. Lincoln Chafee signs a new campaign finance reform law requiring disclosure of principal funders to Super PACs and other independent groups, including tax-exempt groups, that spend more than $1,000 on campaign ads or “electioneering communications” in state elections. The Transparency in Political Spending Act, jointly developed by the governor, the legislature Democratic leadership, public interest groups such as Common Cause, defines “electioneering communications” as print, broadcast, cable, satellite, or electronic media communications that unambiguously identify and either support or oppose a candidate, that run within 60 days of a general election or within 30 days of a primary election and that can reach an audience of 5,000 or more. Independent groups are required to identify all donors of more than $1,000 during a given year.

South Dakota:

David and Charles Koch. Artwork (CC): DonkeyHotey.

-

- Dec. 2015 – Take It Back, a South Dakota citizens movement, wins certification for a popular referendum in November 2016 on a proposal to impose tight disclosure requirements for contributions to candidates or parties “of anything of value” exceeding $100. The measure, developed in association with Represent.Us, a national reform organization, would require independent groups to speedily disclose expenditures of more than $100 used to “influence any election for a state office or ballot initiative” and to list the top five contributors on political ads and communications made within 60 days of an election.

- Summer 2016 – Political network of billionaire Koch brothers launches campaign to defeat referendum initiative that would expose MegaDonors like Charles and David Koch of Wichita, Kansas, whose network has moved tens of millions into political campaigns through stealth channels. Americans for Prosperity, linchpin of the Koch political network, has funded a new front organization, “Defeat 22,” to fund radio ads and mailer campaigns attacking state Initiative 22 that calls for disclosure of political expenditures as well as offering $100 “democracy credits” to all voters to offset and dilute the power and influence of super-rich campaign funders.

- Nov 8, 2016 –A slim 52% majority of South Dakota voters approve IM-22, a ballot measure that requires greater transparency on political spending, imposes limits on campaign donations by lobbyists and provides $100 in democracy vouchers to all voters to donate to candidates of their choice. The victory came in spite of the voters’ rejection of other reform measures such as a non-partisan primary and setting up a multi-party independent commission to be in charge of remapping state legislative districts. The victorious citizens reform movement was led by Rick Weiland, an unsuccessful candidate for the U.S. Senate in 2014, and Drey Samuelson, former chief of staff to retired Democratic Senator Tim Johnson, but it also had the backing of prominent Republicans such as former Senate Majority leader Dave Knudson, former State Treasurer David Volk, former State Senator Don Frankenfeld, and Rick Knobe, former Republican Mayor of Sioux City, now a political independent.

- Dec 8, 2016 –South Dakota Circuit Judge Mark Barnett put implementation of IM-22 on hold by issuing a preliminary injunction at the request of a group of two dozen Republican lawmakers and others who filed a lawsuit against the state. Foes of the measure contend that provisions of the law including an ethics commission, public campaign funding, and limitations on lobbyist gifts to lawmakers violate either the South Dakota constitution or the federal constitution or both. Attorneys representing the state and sponsors of the ballot measure argued against the court ruling, asserting that IM-22 is constitutional.

- Feb. 17, 2017 -South Dakota Republicans kill voter-approved political reform initiative that called for an ethics commission to oversee state politics, sought to impose limits on lobbyists’ campaign donations, and would provide democracy vouchers for average voters to donate small funds to candidates of their choice. Republican leadership of state legislature, caught off-guard by citizen reform movement that backed reform measure IM-22, claimed a state of emergency to justify its nullification of a 52% popular vote majority for the anti-corruption measure. Republican Gov Dennis Dugaard signed the repeal bill which denies voters an opportunity to vote again on the same measure.

- Dec. 2015 – Take It Back, a South Dakota citizens movement, wins certification for a popular referendum in November 2016 on a proposal to impose tight disclosure requirements for contributions to candidates or parties “of anything of value” exceeding $100. The measure, developed in association with Represent.Us, a national reform organization, would require independent groups to speedily disclose expenditures of more than $100 used to “influence any election for a state office or ballot initiative” and to list the top five contributors on political ads and communications made within 60 days of an election.

Texas:

- Oct. 29, 2014 –Eight-member Texas Ethics Commission adopts a rule requiring nonprofits to register as a Political Action Committee and disclose their donors if they spend 25% or more of their budget on political activity or if more than 25% of their contributions are political in nature. The rule, similar to legislation adopted in 2013 by the Texas legislature and vetoed by Gov. Rick Perry, is quickly challenged in court. The Ethics Commission has been working to clarify how that 25% should be calculated.

- Oct. 5, 2015 – Texas Ethics Commission adopts another rule targeting clearly political activity by 501(c)4 organizations and sidestepping ineffective test of whether electioneering communications use such telltale words as “vote” “elect” or “against.” New Commission rule requires disclosure of funders for nonprofits running ads or distributing communications within 30 days of an election that are “susceptible to no other reasonable interpretation than to urge the passage or defeat” of a measure or a candidate.

Vermont:

- Jan. 12, 2014 – Eight years after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Vermont’s campaign spending laws, the state legislature passes new campaign finance regulations setting low campaign spending and contribution limits and strong disclosure requirements. The law, signed by Gov. Peter Shumlin (D), requires a report within 24 hours by any person, political action committee, independent group, candidate, or party that spends $500 or more on mass media within 45 days of any election. Donors who give $2,000 or more to a party, political action committee, or independent group that engages in electioneering communications must be identified in that political ads, in any medium. A political action committee spending $1,000 or more during a two-year election cycle must file full a campaign finance report containing a list of all contributions and expenditures.

Washington:

Integrity Washington leaders include Ben Stuckart (D) President of Spokane City Council; Kathy Sakahara, League of Women Voters of Washington; Greg Moon, Co-Chair, Seattle Tea Party Patriots Integrity Washington.

- Spring 2016 – An unusually broad left-to-right cross-partisan political coalition joins forces to push for a popular referendum on the Washington Government Accountability Act to offset campaign MegaDonors by empowering average voters with democracy vouchers, deter influence-peddling in election campaigns by lobbyists and state contractors, and expose dark money donations with tighter campaign disclosure rules. Backing the petition drive for this measure are such national organizations as Every Voice and Represent.Us; conservative groups such as Take Back Our Republic and Seattle Tea Party Patriots; and Washington State organizations such as Fix Democracy First, the League of Women Voters of Washington, the Progress Alliance of Washington and Wash PIRG. The petition drive, which began March 21, 2016, must gather at least 246,000 valid signatures before July 8 to quality this initiative for the November 2016 ballot.

- If adopted, the proposal (I-1464) would provide each voter with three $50 democracy credits to contribute to candidates of his/her choice, funded by closing a loophole in state sales taxes for certain out-of-state shoppers. Participating candidates must agree to significantly lower limits on private donations and the use of their personal funds. The new measure zeroes in more closely on the five top donors to political campaigns, independent groups, or electioneering ads and communications. Current law requires disclosure but donors can be masked by routing donations through shell Super-PACs or other funding conduits. This proposal requires that electioneering communications identify the root sources of the five main contributions, whether corporations, unions, or individuals. The Act, similar to a measure passed by Seattle voters in 2015, would bar lobbyists and public contractors from contributing more than $100 to candidates for any office they lobby or that has control over public contracts. It also seeks to reduce revolving door political influence by requiring a three-year cooling-off period before former elected or appointed officials or high-level public employees can become involved in paid lobbying.

- Nov 8, 2016 – By a 53.5% majority, Washington rejected a campaign reform initiative (I-1464) that would have provided each voter with three $50 democracy vouchers to donate to candidates of their choice, significantly strengthened the state’s disclosure regimen for campaign donations and imposed limits on campaign funding by lobbyists and companies doing significant business with the state.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.