Will Campaign Reform Make It to the White House?

Washington – In its focus on presidential personality politics, the mainstream media has overlooked a stunning watershed in U.S. political history – campaign reform has jumped this year from a fringe issue, popular with grass roots reformers, to a high profile cause embraced by a major White House contender.

This past week, Hillary Clinton promised that if elected, in her first 30 days, she “will propose a constitutional amendment” to overturn the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision that unleashed unlimited corporate spending in election campaigns and to restore the power of Congress and the states to regulate campaign money. Clinton vowed to appoint justices who understand that Citizens United “was a disaster for our democracy” and to back legislation to empower small donors and require federal contractors to report their campaign donations.

Clinton’s pledge, wooing the legions of Senator Bernie Sanders, echoes Republican Presidents Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft who thundered against the corrupting influence of corporate money and Robber Baron donors in American election campaigns roughly a century ago. They eventually got corporate campaign donations outlawed in 1907 – until the Citizens United decision in 2010.

Hillary Clinton vows action vs “Citizens United.” (CC) Ted Eytan

But never before in modern campaign history have multiple contenders for the presidency openly embraced the populist charge that American democracy has been corrupted by the mega-million donations from billionaires and corporations, and then urged reforms to re-establish a more level playing so that the voices of ordinary voters can be heard.

Vermont’s Senator Bernie Sanders, of course, broke the ice. It was his clarion call for a political revolution that fired the insurgent Sanders candidacy and enabled him to win 13.1 million votes in Democratic primaries and carry 23 states. Among more than a score of presidential contenders, Sanders alone staked his bid on a populist demand for sweeping reforms to restore campaign funding limits, to break up partisan gerrymandering of congressional districts, and to enact voter protections and public financing of campaigns.

Republicans, Too, Catch the Reform Bug

But during the primary campaign, the germ of political reform spread far beyond Bernie. It cropped in the stump speeches and debate sallies of Republicans Donald Trump, Jeb Bush, John Kasich, and Lindsay Graham, as well as in Hillary Clinton’s appeals to Democratic primary voters, despite her close ties to the Wall Street establishment that pumps big money into Democratic campaigns. Among the major contenders, only conservative Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio resisted the reform bug.

Trump never spelled out any reform agenda, but he repeatedly mocked his Republican primary rivals as Lilliputian candidates beholden to MegaDonors aiming ultimately to buy influence with their contributions to the candidates and their candidate SuperPACs, which Trump derided during the primaries but may welcome in the general election campaign.

Donald Trump, (CC) Darron Birgenheier

“People love the fact that I’m putting my own money in,” Trump bragged to voters, “unlike Bush, who is totally controlled by these people, and unlike Hillary and honestly Marco and everybody. Ted Cruz, he’s got a lot of people putting big money in.”

When he was booed during the Republican debate in Manchester, New Hampshire, Trump scored points by telling television viewers that the live audience in the hall was dominated by “donors and special interests. The reason they’re not loving me is, I don’t want their money.” But Trump never went so far as to say how he might try to fix the system.

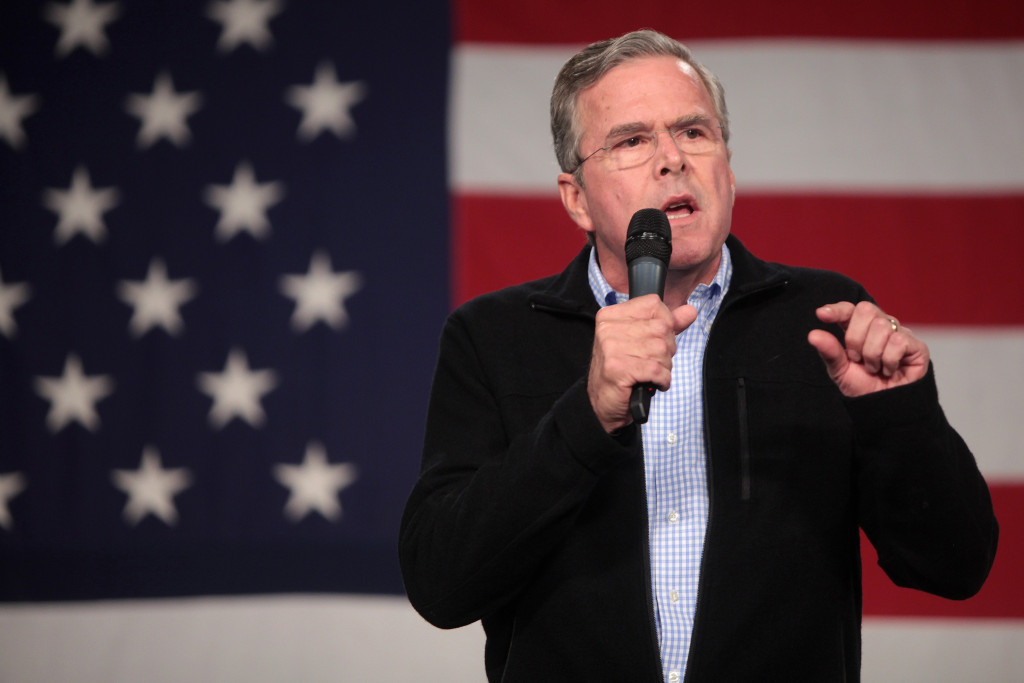

Jeb Bush Flip-Flops on Super-PACs

The biggest flip-flop came from Jeb Bush. Before bowing out of the race, Jeb swung from champion fund-raiser to caustic fund rebuker. Having personally compiled the largest bankroll in SuperPAC history, more than $100 million, Bush underwent a battlefield conversion. “This is a ridiculous system we have now,” he told CNN, “where you have campaigns that struggle to raise money directly and they can’t be held accountable for the spending of the SuperPAC that’s their affiliate” – which is precisely what candidate Bush had been doing since early 2015.

Gov. Jeb Bush, (CC) Gage Skidmorer

Under relentless fire from Trump, Bush flipped. Once eager to keep donors secret, he came out for “total transparency” on campaign funders. To stem the uninhibited flow of campaign cash, Bush said he would try to switch Supreme Court rulings or, if necessary, to amend the Constitution, thus endorsing the position already taken by another GOP presidential hopeful, South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham.

“The ideal situation would be to overturn the Supreme Court ruling that allows for effectively unregulated money,” Bush declared in New Hampshire. But if that fails, “there is a growing sense that we need to amend the Constitution.”

Texas Senator Ted Cruz, who raised more than $40 million in Super-PAC funds, was not buying that line. As the most outspoken foe of campaign finance reform among the candidates, Cruz favors unlimited campaign spending, equating campaign dollars with free speech. Florida’s Senator Marco Rubio, another multi-million-dollar fund-raiser, was also skeptical. He sidestepped the issue of reform, sniping that the mainstream media is ”the ultimate SuperPAC.”

Kasich: Gerrymandering is the Big Evil

Among Republicans, Governor John Kasich has been the strongest advocate for supporting small campaign donors to counteract billionaires, and for fighting against partisan gerrymandering, a well-entrenched strategy of Republicans in his home state of Ohio and a major vehicle for achieving the Republican majority in the House of Representatives.

“We need to eliminate gerrymandering,” Kasich told the Columbus, Ohio Dispatch. “We’ve got to figure out a way to do it. We’ve got to have more competitive districts. That, to me, is what’s good for the state of Ohio and good for the country.”

Both Sanders and President Obama also advocated gerrymander reform as essential to restore American democracy by giving voters more authentic choices in elections and to re-establish a more level playing field. But Hillary Clinton did not adopt gerrymander reform.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, (CC) Phil Roeder (cropped)

After The Election: What Happens?

Where Clinton and Sanders have now come together is in promoting a constitutional amendment to overturn the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision; in advocating tough new disclosure laws requiring that all campaign spending be rapidly made public so that voters can see who bankrolls whom; in calling for a federal matching fund system to multiply the impact of small donor contributions; and in protecting voters rights at the polls.

Until this week, the key question was whether the embrace of reform by presidential candidates would translate into action after the election is over and give new impetus to reform proposals that have been trapped in Congressional gridlock. Democrats are heavily in favor, but so far all but one or two Republicans in Congress have been staunchly opposed.

Against that backdrop, the sheer fact that several Republican presidential contenders have given their blessing to reforms to fix our democracy signals a significant shift in the political terrain. Reform has now won bipartisan acceptance at the summit of American politics, and if Hillary Clinton wins, it will have a committed advocate in the White House – as well as the influential voice of Bernie Sanders in the Senate to hold her feet to the fire.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.