Can We Fix the Electoral College?

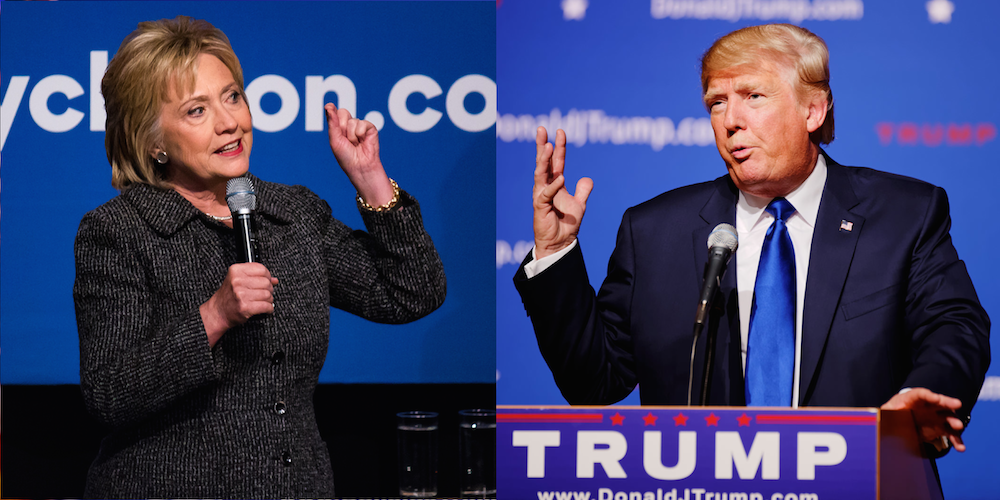

Washington – The populist revolt against the Electoral College burst into action after Al Gore won the nationwide popular vote for president in 2000 but George W. Bush won the Presidency. It gained new momentum after Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump by 3 million votes in 2016, but Trump won the White House in the Electoral College.

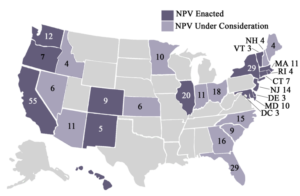

Frustrated by a two-century-old mechanism that has twice foiled the popular majority in just 16 years, legislatures in 15 states and the District of Columbia, have joined forces to try to assure that in the future the popular vote winner will gain the Presidency.

These states have formed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, pledging to cast their electoral votes for the nationwide popular vote winner rather for the highest vote-getter in their own state – if enough other states agree to do the same.

In other words, rather than seeking to abolish the Electoral College, which would require a constitutional amendment with little chance for passage, the popular vote reform movement has devised what the digital world calls “a work-around.”

Progress Report – 70% of the Goal

To work, this strategy requires firm legal commitments from states with the power to cast at least 270 of the nation’s 538 electoral votes. With legislative action this year by Colorado, Delaware,New Mexico and Oregon to join the compact, the popular vote movement has amassed a total of 196 electoral votes – 74 short of the total needed to award the White House to the national popular vote winner.

Oregon’s Democratic Gov. Kate Brown, signing her state into the interstate compact, asserted that this strategy would force both parties to contest more states, like Oregon and thus’increase voter turnout.“I think it will encourage candidates to spend more time in states like ours,” she said.

But in Nevada, Gov. Steve Sisolak, also a Democrat, took a contrary view, as a he vetoed a similar bill passed by the Nevada legislature. Sisolak feared the popular vote strategy “could diminish the role of smaller states like Nevada “ and “force Nevada’s electors to side with (the national vote winner), rather than the candidate Nevadans choose.”

Another dozen states – more than enough to hit the goal – have started to take action on the popular vote compact. Nine have legislatures controlled by Republicans, once in favor of the popular vote reform but now hesitant instead of moving ahead.

Trump Flip-Flops on the Electoral College

What’s the hold-up?

Donald Trump.

Historically, Donald Trump was no fan of the Electoral College. At 12:45 am on Nov 7, 2012, just after Democrat Barack Obama was declared the winner over Republican Mitt Romney, Trump attacked the Electoral College in a raging tweet: “The electoral college is a disaster for a democracy.” Trump cranked up a tweet storm rampage, slamming the 2012 election as “a total sham and a travesty” and deriding the “phoney electoral college.”

Four years later, Trump flip-flopped. One week after the Electoral College rescued him after he had lost the popular vote, Trump no longer thought it a “disaster” but extolled it as a miraculous mechanism. “The Electoral College,” he glowed, “is actually genius in that it brings all states, including the smaller ones, into play.”

Awkward for Republicans

That’s not what some important Republicans had been saying. In 2014, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich warmly endorsed the popular vote compact. With a Democrat in the White House, Gingrich complained that the Electoral College was pushing presidential campaigns to concentrate on a few states and ignoring all the others – bad for democracy.

Case in point – the Trump-Clinton campaign in 2016: Two-thirds of presidential campaign events occurred in just six battleground states – Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia and Michigan. Their electoral votes, up for grabs, were decisive. Heavily populated states like California, New York, Texas, Illinois, Massachusetts and Georgia and all smaller states were almost totally ignored by campaigns because they were seen as inevitably red or blue, and not worth fighting over.

Case in point – the Trump-Clinton campaign in 2016: Two-thirds of presidential campaign events occurred in just six battleground states – Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia and Michigan. Their electoral votes, up for grabs, were decisive. Heavily populated states like California, New York, Texas, Illinois, Massachusetts and Georgia and all smaller states were almost totally ignored by campaigns because they were seen as inevitably red or blue, and not worth fighting over.

That hard reality helped dmotivate eight former leaders of ALEC, chairs of the the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, to back the popular vote compact.“This is a state rights issue, a true federalist solution to the current problem where 4 out of 5 Americans are ignored by presidential candidates,” ALEC’s leaders declared.

That mindset prompted 16 Republican lawmakers in the Oklahoma senate and 20 Republicans in the Arizona house to back legislation adopting the national popular vote compact. It got action moving in other Republican-dominated states like Georgia, Kansas, Ohio and North Carolina.

But after Trump’s election, Republicans had a change of heart. Popular vote reform legislation in Oklahoma and Arizona was killed and bills in other red state legislatures were shelved. Gingrich and the ALEC leaders fell silent.

Expect More Questionable Elections

But without some reform, political scientists say, the problem will haunt us because the Electoral College is likely to produce more “wrong winners,” that is, popular-vote losers. The main reason, says Ohio State University Professor Edward Foley, is the impact of third- and fourth-party candidates, which often get enough votes to deny a popular vote majority to any candidate in multiple states.

In 2016, for example, Donald Trump won 101 electoral votes in six states where he received less than 50% of the popular vote – Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Nonetheless, those states awarded Trump all of their electoral votes. This winner-take-all system for a candidate who gets only 45% or 46% of the popular vote in state after state widens the gap between the Electoral College vote and the national popular vote.

What’s more, Professor Foley contends, winner-take-all for a plurality winner violates what the Founding Fathers intended in the Constitution’s 12th Amendment, which gave us the current Electoral College. He quotes Senate debates in which, the Amendment’s advocates argued that “the election of a President should be determined by a fair expression of the public will by a majority.” Not necessarily a national popular vote majority, says Foley, but an electoral vote majority based on majority support within each state – not just a plurality.

Our current system falls far short of that. Political scientists have calculated that it is theoretically possible to win a 270-vote Electoral College majority by winning as little as 23% of the national popular vote. Extremely unlikely, but possible. In the three-way race of 1992, Bill Clinton won the Presidency with 43.3% of the popular vote.

To better conformity with the 12th Amendment and achieve broader, healthier consensus behind the ultimate winner, Foley raises several potential reforms, such as barring any candidate from receiving all of a state’s electoral votes without winning a state’s popular vote majority; or allocating electoral votes by congressional district, as Maine and Nebraska now do; or rank choice voting to re-allocate popular votes initially cast for third- and fourth-place candidates among the top two, so someone winds up with a majority.

But for now, momentum is behind the national popular vote compact. And based on past experience, that reform might get a new shot in the arm from Republicans if a Democrat wins the White House in 2020.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

1 Comment