3 Ways to Fight Extremism, Bolster the Middle

Washington – With the election just days away, are you getting tired of the scaremongering and mud-slinging in the presidential campaign? How about some good news for a change?

Good news about political reforms to make American elections fairer, more transparent, and more inclusive, and to help rebuild the political middle, so desperately missing in today’s bitterly polarized politics.

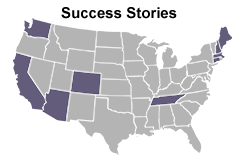

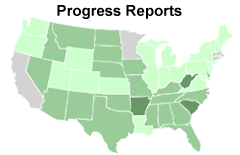

From the mainstream media, you’d never know anything was happening, but from Florida to Alaska, and in states like Missouri, Massachusetts, and Virginia, grassroots citizen movements are pushing for adoption of political reforms on Nov. 3, and were it not for the coronavirus, there would be a lot more.

What made it onto the ballot are different reforms in different states. But they share some very important common threads – more voice and choice for average voters and more ways to combat political extremism and rebuild the political middle.

Independent Voters Want More Voice

One strategy is to give more voice and clout to political independents – the fastest growing group on our political landscape, the mass of Americans in the middle who have become disenchanted with political parties and partisan warfare.

Back in 2004, only 27% of Americans identified themselves as political independents to the Gallup Poll. This fall that number has shot up to 42% and it’s even higher (44%) among younger voters under 40. And of course, that boom means that our two big parties have been shrinking – Republicans down from 38% to 28%, Democrats down from 35% to 27%.

Florida Capitol Building – The state has 3.6 million independent voters.

But there’s a fly in the ointment. That burgeoning mass of independents is shut out of party primaries that are often the decisive elections for congress, the state legislature, and other offices. And independents want in on the action.

Take Florida, which now has more than 3.6 million independents – NPA’s, they call them, No Partisan Affiliation. In the Sunshine State this year, a broad grassroots movement called All Voters Vote is campaigning for the adoption of a non-partisan primary for all statewide offices and the legislature to open the door to independent voters and to reduce the “partisan extremism” that is fostered by political party primaries.

What the Florida reformers propose is one big, wide-open primary election where Republicans, Democrats, Greens, Libertarians, all candidates compete and all voters vote, including independents. The top two vote-getters for each office in the primary qualify for the general election. No party gets a lock on any office.

Alaska – Attacking Dark Money and Party Primaries

Five thousand miles away in Alaska, they’ve got an even more ambitious reform plan. With more than 54% of Alaskan voters declaring no party affiliation, a trans-partisan citizens coalition, Alaskan for Better Elections, is also calling for a non-partisan primary election, open to all six of Alaska’s political parties, to be followed by a so-called “instant runoff ” using rank choice voting in the general election.

Anchorage skyline – 54% of Alaska’s voters are independents

The Alaska reform would also ban dark money, require disclosure of the true donor of any political contribution of $2,000 or more and it would put Alaska on record – with 19 other states – urging Congress to initiate a U.S. constitutional amendment to restore the power of Congress and the states to regulate campaign expenditures, thereby overturning the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in the Citizens United case.

Former state Rep. Jason Green, a political independent who co-chairs the reform coalition with a Republican and a Democrat, describes the Alaska reform as “a three-pronged attack on making our elections better.”

How Rank Choice Voting Fights Extremism

The newest prong is rank choice voting. In this system, voters rank all the candidates for each office, as their first, second, or third choice, etc The ultimate winning candidate must get a true majority, 50% plus 1. If no one gets 50%-plus on the first vote-count, the bottom candidate drops out and his or her votes are reallocated to their voters’ second choice. If there’s still no majority winner, they do it again. The low candidate drops out and those votes are reallocated, until finally some candidate gets 50% plus one.

Rank choice voting advocates say that system reduces extreme partisanship by pushing candidates to appeal to voters all across the political spectrum in order to compile that magic majority and also, as one proponent put it, by making sure that “an extremist can’t slide into office thanks to vote-splitting” among other candidates.

It’s widespread in Europe. It’s being used in Maine and its popularity is growing in the U.S. This year, rank choice voting proposals are on the ballot in Massachusetts for state and congressional elections and in St. Louis for municipal elections.

“The Integrity of Democracy Is at Stake”

A third major push for fairer elections and against partisan extremism is the ballot initiative in Virginia for gerrymander reform. In 2018, four states adopted gerrymander reform – Michigan, Missouri, Colorado, and Utah. To prevent a conflict-of-interest among politicians, voters in those states took the job of drawing election maps out of the hands of elected politicians in the legislature and turned it over to independent commissions comprised of citizens of all political stripes, evenly divided.

This year, Virginia is the only state doing gerrymander reform, and it is going just halfway, mainly because legislators had a hand in drafting the reform plan and they didn’t want to give up all their power. The Virginia plan turns election map-making over to a 16-member commission. composed half of lawmakers and half of ordinary citizens, eight Republicans and eight Democrats.

Former Republican U.S. Senator Jack Danforth

In Missouri, reformers are fighting a rearguard battle for gerrymander reform against the Republican-dominated state legislature. In 2018, the Clean Missouri reform movement won a 62% majority for non-partisan gerrymander reform, but this year, the legislature is trying to gut the reform and restore the old gerrymander system run by lawmakers themselves. They’ve put a new proposal on the ballot this fall, which reformers deride as “Dirty Missouri.”

One outspoken foe of letting legislators get back into stacking election maps is an icon of Missouri Republican politics, former three-term U.S. Senator Jack Danforth, and he minces no words warning of the dangers of old-style gerrymandering to the majority of voters in the political middle and to good government.

When politicians draw their own maps, says Danforth, extremist voters dominate party primary elections, and “incumbents get pulled toward the extremes in their own party. The majority of voters — the moderates who make up the center of the citizenry — get ignored….If Clean Missouri gets dumped this year, you’ll just see more partisanship and extreme politics than ever.” With a message that echoes nationwide, Danforth concludes: “The integrity of Missouri’s democracy is at stake.”

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.