Inclusive Capitalism:

Inclusive Capitalism:

Strategy vs Inequality

Inclusive Capitalism:

Inclusive Capitalism:Strategy vs Inequality

Confronting “The Capitalist Threat to Capitalism”

In the years since Occupy Wall Street raised the cry of the 99% against the 1%, economic inequality has been the top issue on America’s economic agenda. More and more voices, even at the commanding heights of business, say the US economy must take action to mitigate Corporate America’s dogma of shareholder capitalism that has fueled the hyper-concentration of wealth in America over the past three decades. Fortunately, some moves are afoot to foster a more inclusive, share-the-wealth brand of capitalism.

Shareholder capitalism may be institutionally entrenched but it is ideologically on the defensive. Even at the pinnacle of the business pyramid, there is angst about what Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, has called “the capitalist threat to capitalism” – a nagging worry that drew major global investors who control $30 trillion in assets to London in May 2014 for a conference on “Inclusive Capitalism,” organized by Lynn Forester de Rothschild.

In a keynote essay, Paul Polman and Lady Rothschild observed that market capitalism “has often proved dysfunctional in important ways. It often encourages shortsightedness, contributes to wide disparities between the rich and the poor, and tolerates the reckless treatment of environmental capital. If these costs cannot be controlled, support for capitalism may disappear.”

Larry Fink, CEO, Blackrock. (CC) Financial Times.

Stop Catering to Shareholders, Think Long-Term

An even stronger critique of Corporate America’s short-term focus on profits and stock prices has come from Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock, one of the world’s largest investment funds. In a blunt letter to 500 U.S. CEOs in April 2015, Fink told them to stop catering to shareholders and spending so much of their profits on stock buybacks because that was hurting their businesses and hampering overall U.S. economic growth. “Returning excessive amounts of capital to investors,” Fink asserted, “sends a discouraging message about a company’s ability to use its resources wisely” and to develop a long-term growth strategy.

In the wake of the massive cut in corporate taxes pushed by President Trump in December 2017, Larry Fink once again told American CEOs to commit more resources to long-term corporate and economic growth and not get pressured by activist investors in heaping quick short-term payoffs to stockholders. With corporate surveys showing four out of five corporations will return most of their tax windfall to investors rather than workers, Fink warned in a new letter to CEOS that “society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose,”

When Trump, House Speaker Paul Ryan, and other Republican leaders were selling their $1.5 trillion tax cut to Congress and the public, the talk was all about what Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin predicted would be a “massive investment” in growth and jobs. And there was a spurt of investment for a while. But now, figures show that far more corporate money – $579 billion – went into stock buybacks to fatten the portfolios of super-rich investors. Plus another $421 billion in dividends – $1 trillion in toto. Stock buybacks are a favorite tactic of shareholder capitalism – corporations buying back their own stock to jack up the stock price enabling Wall Street and its pet clients to reap enormous profits. Exhibit A – Apple. In 2018, Apple spent $63.9 billion on buybacks as a boon to its investors but only $10.5 billion on capital investments that would help its productivity and its workforce.

Wall Street brokers make the pitch that stock buybacks are a good deal for most investors but that’s not what recent academic and market studies say. They throw cold water on that pitch. They report, for example, that the nearly $570 billion that American corporations spent in 2015 on buying back their own shares worked out poorly for most investors. Some fast-moving hedge funds and billionaire activist investors made quick killings, but more typical investors lured to big buyback companies fared badly over time because companies that bet heavily on buybacks typically went sour, whereas the stocks of companies that avoided buybacks actually enjoyed better longer-term performance.

Worker-Friendly CEOs Change Direction

There is in fact, a maverick group of high-profile CEOs at companies like Costco, Aetna, Patagonia, McKinsey, Ben & Jerry’s, and Avon Products who have ignored the dictates of shareholder capitalism in favor of a more inclusive brand of business leadership. Popular pressure, too, pushes in that direction, with shareholder revolts breaking out at many corporate annual meetings.

In the summer of 2014, when a worker-friendly, consumer-friendly CEO in the New England supermarket chain Market Basket was ousted by owners demanding higher shareholder returns, it touched off a revolt. Grocery store workers walked off the job and shoppers boycotted the chain in a show of grassroots power until the old CEO was put back in charge.

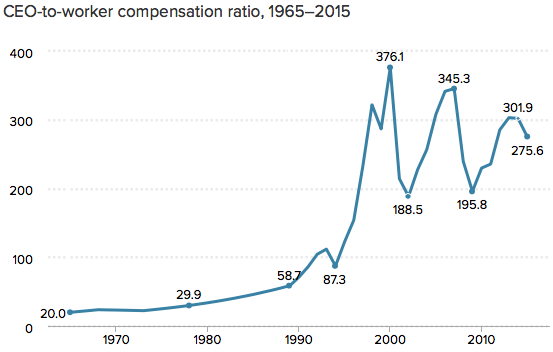

Source: Economic Policy Institute

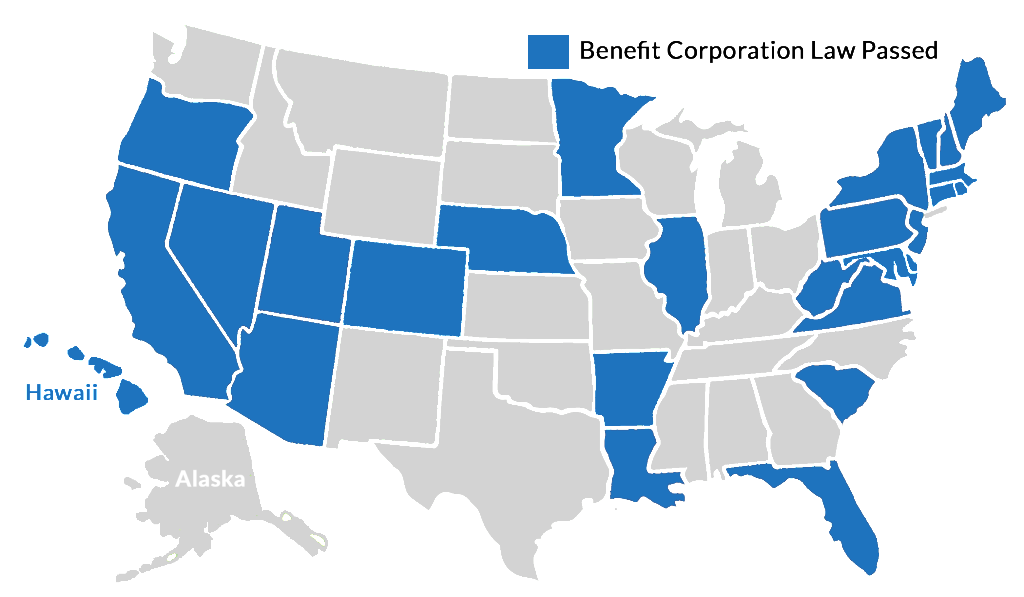

With strong bipartisan political support, 27 states have enacted laws in the past few years to legitimize the formation of Benefit Corporations, providing Legal protection for CEOs and company boards to pursue goals other than maximizing profits, such as protecting the environment, serving society, and making decisions that serve workers and local communities as well as shareholders.

In Portland, Oregon, the city council voted on Dec. 7, 2016, to impose a 10% surtax on companies whose CEO is paid more than 100 times as much as an average worker, and a 25% surtax when the CEO’s pay is more than 250 times the average workers pay. The tax depended on federal requirements that publicly traded companies calculate and report on how their chief executives’ compensation compares with their median workers’ pay. Portland’s corporate surtax was the brainchild of City Commissioner Steve Novick, a Democrat. “When I first read about the idea,” Novick said, “I thought it was a fascinating idea. It was the closest thing I’d seen to a tax on inequality itself.” But the Trump Administration has blunted the impact of Portland’s move.

Hide and Seek on CEO Pay

One of the major reforms mandated by the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial regulatory law ordered the Securities and Exchange Commission to adopt a rule requiring every company to report the ratio of its CEO’s pay to that of an average employee. Business lobbyists fought for five years to prevent that rule from being issued. Finally, on Aug. 5, 2015, the SEC voted 3-2 to require publicly listed companies to disclose the details of CEO pay and show the huge pay gaps between CEOs and average employees.

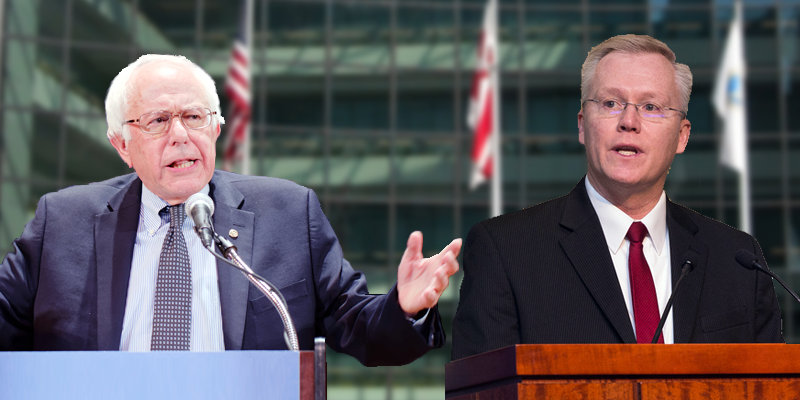

Senate Democrats, led by Bernie Sanders, attack GOP Acting SEC Chair Michael Piwowar for delaying expose of CEO pay. Image by Reclaim. Sanders source: (CC) Michael Vadon. Piwowar by(CC) SEC

That rule was scheduled to take effect in January 2017. But Trump’s acting chair of the SEC, Republican Commissioner Michael Piwowar, ordered postponement on grounds that companies were having “unanticipated compliance difficulties.” For seven years, corporate chiefs had stalled exposure for their soaring pay packages by arguing that it was too hard for companies to calculate the ratios with average worker pay. Piwowar added another stall by calling for a new comment period on the rule.

Piwowar’s delay triggered howls on Capitol Hill. Seven Democrats, led by Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, sent Piwowar a stinging letter saying that were “alarmed” by the delay and demanding that the SEC “allow full implementation of the CEO-to-worker pay ratio disclosures” at once. The SEC, they noted, had already gotten 287,400 comment letters, “the vast majority of which strongly supported the rule.”

Moreover, the Democrats pointed out that the yawning gap between CEO and worker pay had widened sharply since the Dodd-Frank law was enacted. In 2015, they noted, the CEO of an S&P 500 company made 335 times the pay of an average employee -nearly as much pay for a CEO in one day as the worker made in an entire year. In 2016, the highest paid CEO, Thomas Rutledge of Charter Communications, got a $98 million pay package – 2,617 times the average American worker’s pay of $37,632, according to data from the AFL-CIO.

Wall Street VIPs – Lloyd Blankfein, CEO of Goldman Sachs, and Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase.

What’s more, the financial collapse of 2008 had spawned a public outcry for controls on skyrocketing executive packages at Wall Street’s super banks and astronomically paid market traders. Regulators and lawmakers contended that that lucrative bonus system on Wall Street poses a danger to the nation’s economy by motivating some bankers to take excessive risks.

In April 2016, regulators issued new rules aimed at curbing the casino mentality on Wall Street by regulating how major financial firms structure their pay packages and by forcing the highest-paid executives and bank traders to wait at least four years to receive parts of their bonuses to make sure that highly-touted deals actually generated long-term gains. In some cases, banks would be required to claw back bonuses from traders and executives who took risks that seemed profitable in the short run but eventually caused big losses. But President Trump’s moves for deregulation have stalled the measures drafted by the Obama Administration.

“You Cannot Let Wall Street Run Your Business”

Nonetheless, some business leaders have started to implement q more equitable and inclusive capitalism. Warren Buffett, the multi-billionaire chair of Berkshire Hathaway holding company, has openly derided the ego-driven, power-hungry CEOs and the aggressive, self-serving financial “acrobatics” and “dubious maneuvers” of Wall Street banks. The best CEO, Buffett declared in his annual reporters to shareholders, stays humble, admits personal mistakes, “knows his limits,” recognizes that “character is crucial” and gives credit to people far down the line for corporate success.

That description pretty well fits Jim Sinegal, who practiced inclusive capitalism while he was running retail giant Costco from 1983 to 2012, even though competitors like Wal-Mart catered to Wall Street and their richest owners.

“You cannot let Wall Street run your business,” asserts Sinegal, a roly-poly marketing genius with a quick, jowly smile and the open, friendly manner of the butcher at your corner grocery. “Business is supposed to be about more than making money. You have an obligation to the communities where you live to provide good jobs, good careers, and be honest with your customers so that these communities can count on you.”

Sam Walton, Wal-Mart Founder, and Jim Sinegal, CostCo Co-Founder & Fmr. CEO

“Employee Friendly Is Smart Business.”

Although other retailers have copied the cost-cutting, low-wage, fast labor-turnover model of Wal-Mart, Sinegal took Costco in the opposite direction. He offered higher pay, better benefits, steady work, and a middle-class career path. In 2011, when Wal-Mart cut back its health benefits, saying that costs had become prohibitive, Sinegal maintained Costco’s more generous benefits.

“We try to provide a very comprehensive health-care plan for our employees,” he said. “Costs keep escalating, but we think that’s an obligation on our part. We’re trying to build a company that’s going to be here 50 and 60 years from now. We owe that to the communities where we do business. We owe that to our employees, that they can count on us for security.”

To Sinegal, a company’s ethical values, its culture, are paramount. “It drives every decision you make,” he asserts. He recalls, for example, when he negotiated a great bargain on a mass shipment of Calvin Klein jeans and could have reaped a huge profit by sticking to Costco’s regular price of $29.99. Instead, Sinegal dropped the price to $22.99, passing along his savings to customers. “That’s company culture. It’s also discipline,” he explains. “Going for the quick profit is easy. It’s like heroin. But once you decide to make the extra $7 a pair of jeans, then it’s open season on everything else. Your culture is gone. It’s our commitment to our customers.”

True to Costco’s culture, Sinegal took an annual salary of $2 million while Wal-Mart’s CEO got paid $20 million. And he treated Costco’s 140,000 workers well. “Employee friendly is smart business,” Sinegal insists. “We pay the highest wages and charge the lowest prices and still make money. So we must be doing something right. We’re getting high productivity. Employees are motivated. We get better performance.” Over the long run, that pays off for shareholders, too. Since 1985, he says, Costco sales are up 13% a year and stock value up almost 17% per year, compounded.

Brand Integrity, Human Relations Before Profits

Other modern American CEOs, too, have made their mark by pursuing inclusive capitalism and visibly putting brand integrity and human relations ahead of profits – James Burke at Johnson & Johnson, Ken Melrose at Toro, David Packard at Hewlett Packard, Dominic Barton at McKinsey & Company, Doug Conant at Campbell’s Soup and Avon Products, and most recently Mark Bertolini at Aetna, the insurance firm.

Other modern American CEOs, too, have made their mark by pursuing inclusive capitalism and visibly putting brand integrity and human relations ahead of profits – James Burke at Johnson & Johnson, Ken Melrose at Toro, David Packard at Hewlett Packard, Dominic Barton at McKinsey & Company, Doug Conant at Campbell’s Soup and Avon Products, and most recently Mark Bertolini at Aetna, the insurance firm.

After reading French economist Thomas Piketty’s tough-minded analysis, Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century that documents the link between investor-first capitalism and the rising tide of inequality, Bertolini decided to try to stem the tide. In early 2015, he gave Aetna’s lowest-paid employees, mostly customer service agents and claims administrators, a 33% raise, from $12 to $16 an hour.

And by giving the Piketty book to all his senior executives, Bertolini signaled that more reform was coming at Aetna. “Companies are not just money-making machines,” Bertolini told The New Yorker. “For the good of the social order, these are the kinds of investments we should be willing to make.”

Hedge-fund billionaire Paul Tudor Jones II has launched a new movement, Just Capital, to rate major companies not on their profits but on how “justly” they treat their workers, society, and the environment. “The wealth gap, that’s the single most important issue in this country,” says Jones, as he puts moral pressure on CEOs to provide better pay, more generous benefits, and happier workplaces and to shame those who resist those goals.

Individual entrepreneurs like Hamdi Ulukaya, a Turkish immigrant who founded the yogurt company Chobani, get the message and take action. In early 2016, Ulukaya sprang a huge surprise on his 2,000 rank-and-file employees – news that he was sharing the wealth by giving them 10% ownership in the company when it goes public or is sold. “I’ve built something I never thought would be such a success,” Chobani explained, “but I cannot think of Chobani being built without these people.”

The Swift Rise of ‘Benefit Corporations’

But rather than relying solely on the philosophical epiphanies or natural inclinations of individual CEOs like Sinegal, Bertolini, or Ulukaya, a burgeoning grassroots movement has emerged to institutionalize more inclusive capitalism by enacting laws that encourage business leaders to adopt broader, more socially oriented goals and strategies.

The movement has risen swiftly. Since 2010, 27 states have enacted laws, usually with wide bipartisan support, that authorize so-called Benefit Corporations, giving them legal authority and protection against any lawsuit claiming that management is neglecting its fiduciary responsibility to maximize profits if it pursues other parallel goals as well. More than 1,500 companies are already registered under these laws.

Although the movement is nationwide, California has become a particular hotbed for Benefit Corporations, like Patagonia, the high profile outdoor wear company founded in 1973 by rock climber and environmentalist Yvon Couinard. Dozens of other small and mid-sized California-based companies have followed suit. One major advantage of legally registering as a Benefit Corporation is that the company’s core values and social purposes are protected long-term, even if company ownership changes.

“A Model That People Can Believe In”

In a parallel development, hundreds of other companies have sought certification as B Corps, cousins of Benefit Corporations that are not legally registered but are technically pedigreed by an independent nonprofit team of technical experts called B Lab. The B-lab team measures each company’s actual performance against specific yardsticks such as treatment of their workforce, relations with their local community, impact on the environment, and the accountability and transparency of management.

If a company gets high enough grades, it is certified as a B Corp. That is a benchmark, giving the company credibility with consumers, investors, employees, and job-seekers that management is serious about pursuing social goals as well as profits. More than 1,200 companies have passed muster to be certified as B Corps, among them Ben & Jerry’s, Warby Parker, the eyeglass firm, Etsy, an online marketplace, and Seventh Generation, a sustainable manufacturer of cleaning and paper products.

Why does B Lab’s seal of approval matter? “I think we’re seeing in society right now the need for corporations to stand for something more,” replies Rob Michalak, a spokesman for Ben & Jerry’s. “The B Corp Movement is an answer to that. It’s a model that can ensure companies provide benefits to society in a way that is transparent, is balanced, and people can believe in.”

That concept got market-tested in April 2015 when Etsy ventured into the lion’s den, daring to raise capital on Wall Street with an initial public offering. To the keepers of Wall Street’s profits-first-last-and-always orthodoxy, Etsy’s generous-to-workers-and-communities business model smacked of ludicrous heresy, doomed to failure. But as one market wag impishly suggested, Etsy’s IPO was “a beautiful test …to see if it’s possible to have a mission beyond money.” Etsy, the B Corp, passed with flying colors. Its stock price nearly doubled on opening day. Even on Wall Street, it seemed, some investors love the idea of a company with a heart.

ESOPs – Fostering Shareholder Democracy

For decades, one time-tested strategy aimed at making American capitalism more democratic has been to empower rank and file employees as significant part-owners of companies, a stratagem that directly confronts the concentration of power at the top of business and also enables family business owners to sell their companies to employees. The concept originated with the “shareholder democracy” stock bonus plans of the 1920s when well-known companies such as Sears Roebuck and Lowe’s invested funds within their employee profit-sharing plans in company stock.

In the 1950s, San Francisco lawyer Louis Kelso pioneered a more far-reaching strategy. He used the first ESOP – Employee Stock Ownership Plan – to transfer ownership of his Peninsula Newspapers, Inc. in Palo Alto, California to his managers and rank-and-file employees. “The employee stock ownership plan was invented to democratize access to capital,” Kelso explained. “In human terms, it is a financing device that gradually transforms labor workers into capital workers. It does this by making a corporation’s credit available to the employees, who then use it to buy stock in the company.” That is how Kelso’s own employees bought him out – a formula later applied at hundreds of other firms.

In the 1950s, San Francisco lawyer Louis Kelso pioneered a more far-reaching strategy. He used the first ESOP – Employee Stock Ownership Plan – to transfer ownership of his Peninsula Newspapers, Inc. in Palo Alto, California to his managers and rank-and-file employees. “The employee stock ownership plan was invented to democratize access to capital,” Kelso explained. “In human terms, it is a financing device that gradually transforms labor workers into capital workers. It does this by making a corporation’s credit available to the employees, who then use it to buy stock in the company.” That is how Kelso’s own employees bought him out – a formula later applied at hundreds of other firms.

ESOPs – Anchor for the Middle Class

Today, roughly 9,000 U.S. firms have ESOP-type plans representing 14.7 million workers and assets totaling close to $1 trillion, according to National Center for Employee Ownership. Such plans exist mainly in small and medium-sized businesses, though a handful have workforces running into the thousands. Typically, employees receive allocations of stock from the company, based on longevity and pay level. They build up employee ownership over time. Today 40% of the ESOP plans now own 100% of the company or are on track to take over full ownership.

ESOP advocates contend that the employee-owned firms get higher performance than conventional firms because they generate greater employee commitment, loyalty, willingness to put in extra effort, and more input on company improvements. ESOPs also give employees greater job security. During the Great Recession, employees in ESOP-related firms were four times less likely to be laid off than those at conventional companies, according to the National Center for Employee Ownership.

Rutgers Professor Joe Blasi, a life-long specialist, and advocate for ESOPs contends that worker ownership is more necessary today as an anchor for the middle class than ever before because middle-class economic power and interests have been so marginalized by top-heavy shareholder capitalism. “The sustaining of a middle class,” Blasi asserts, “requires a capital ownership and a capital income strategy” that gives middle-class employees more say in how companies are run and how the gains of economic growth are shared.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.

Hedrick Smith, who conceived this website and is its principal writer and architect, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning documentary producer for PBS and PBS FRONTLINE.